BACKGROUND

The pandemic has amplified and exacerbated many of the existing challenges facing the field of early childhood education and care (ECEC) and forced the field to innovate and change much of what had become the status quo (Hashikawa et al., 2020). One area in which the status quo has shifted significantly over the past several years is the delivery of professional development for ECEC program leaders. Social distancing, increased workloads, emotional and physical exhaustion, and the pervasive staffing crisis have posed significant barriers to engaging in the intensive and cohesive professional learning experiences that the research literature suggests are critical to the retention of program leaders, the well-being of staff, and positive outcomes for ECEC children and families (Arabella Advisors, 2018; Doherty et al., 2015; Sims et al., 2015; Talan et al., 2014).

As gatekeepers to quality (ensuring access to resources and supports), ECEC program leaders directly impact organizational climate, teaching practices, and family engagement in their programs; thus, role-specific support and professional development are critical to the success of the programs they operate (Bloom & Abel, 2015; Douglass, 2019). Specialized training in leadership strategies and program management is especially critical for new administrators. Administrators who receive support early in their role are more likely to remain in the field, improve the quality of their programs, and continue to grow professionally (Talan et al., 2014).

The McCormick Center has a 30-year history of providing intensive (6-12 months in duration), cohesive (curriculum content is coordinated and builds on previous learning and application), and cohort-based leadership academies. These leadership academies have been consistently evaluated, providing empirical evidence of success in supporting the unique needs of ECEC program leaders, increasing program quality, improving organizational health, and fostering a commitment to ongoing professional growth and achievement (McCormick Center, 2020; Talan et al., 2014).

Before the pandemic, the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership received funding to develop and facilitate a seven-month leadership academy for newly-hired center-based administrators. At first, the traditionally designed leadership academy (in-person, off-site, full-day seminar structure) was postponed in hopes of rescheduling when life “returned to normal” for center administrators. Ultimately, the academy was deconstructed and rebuilt to be delivered virtually.

The leadership academy evaluated in this study provided the challenge and opportunity to rethink the traditional leadership academy delivery model in ways that accounted for an online and remote learning environment, the impact of a staffing crisis that forced administrators to function as teachers in the classroom to maintain ratios resulting in loss of dedicated time for administrative tasks, and amplified feelings of stress and isolation by participants. Was it possible to transform the traditional leadership academy model into a fully virtual one and still achieve the intended learning and professional outcomes? This brief provides an overview of the revised delivery model of a leadership academy for newly-hired administrators and the empirical evidence regarding its success.

THE ACADEMY

This seven-month leadership academy was designed for a cohort of new administrators (less than five years of administrative experience). The theory of change undergirding this academy is that the professional development needs of program administrators differ by their developmental stage (McCormick Center, 2018). The professional learning for novice administrators should begin with leadership essentials—the foundational competencies needed to build or maintain a thriving organization and lead quality improvement efforts at the classroom, program, and organizational levels.

Foundational competencies include knowledge and application of the Whole Leadership Framework, reflective and culturally responsive practices, communication and leadership styles, time management strategies, and intentional leadership practices for a healthy organizational climate (Bloom, 2016; Masterson et al., 2019). These foundational competencies are needed to support the achievement of additional competencies in the administrative and pedagogical leadership areas. The ability to lead effective early childhood programs is directly related to a leader’s self-efficacy. A program leader with high levels of self-efficacy will be resilient and persistent in the face of challenges and setbacks—a critical component of successful leadership (Bandera, 1997; Bloom, 1984).

The original plan for the academy was to offer multiple, full-day, in-person professional development sessions. Those sessions would involve numerous opportunities for self-reflection, small group discussions, peer-to-peer support, and large group discussions. With the onset of the pandemic, the McCormick Center team was forced to rethink the delivery model. The adapted model of the academy consisted of the Ready to Lead Institute (16 half-day remote learning sessions focused on leadership essentials) followed by Continuing the Journey with Aim4Excellence™ (four remote sessions facilitating learning from the asynchronous online modules focused on either pedagogical or administrative leadership).

It was understood that participants would face many challenges navigating the pandemic and staffing shortages while developing their leadership and management skills. Concerns about how to adapt the academy around these challenges were numerous, but three overarching questions rose to the top:

- Would it be possible for participants to focus on and prioritize their learning while also navigating personal and professional challenges? Attendance and completion of all of the components of the academy are critical for success. Sessions, topics, and materials build on each other, and conversations and themes are carried throughout the full academy.

- Would participants value the knowledge and skills targeted in the academy? With so much additional stress and uncertainty facing administrators, it would be challenging for participants to experience the content as timely and meaningful. We worried about how to ensure topics we knew were critical for novice administrators still felt important to participants.

- Would the virtual academy effectively increase knowledge and skills, levels of self-efficacy, and a sense of belonging to a professional community? We wanted to know if we could deliver on our original goals for the academy, despite all of the adaptations we would need to make.

METHODOLOGY

PARTICIPANTS AND PROGRAMS

Participants included 11 program administrators located in a small state. Of the 11 participants, six (55%) identified their role as Director, four (36%) identified their role as Assistant Director, and one (9%) identified their role as Principal. Participants self-identified their gender and racial categories. All participants identified as female. The racial composition of participants included four (36%) individuals who were Asian, three (27%) who were Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, three (27%) who were Multiracial, and one (9%) who was White or Caucasian. The largest groups of participants (four individuals, 36%) reported being between the ages of 40 and 49 or between 50 and 59; another three individuals (27%) were between the ages of 30 and 39. Participants indicated they had worked in the field of early childhood education for an average of 16 years, worked in an administrative position for an average of 4 years, and worked in their current administrative position for an average 1.6 years.

Licensed capacity of the programs ranged between 61 and 120 children in four programs (36%), over 121 children in another four programs (36%), and between 1 and 60 children in three programs (27%). All programs served preschoolers. In addition, seven programs (64%) served toddlers, four programs (36%) served school-aged children, and two programs (18%) served infants.

FORMAL MEASURES

The Training Needs Assessment Survey

The Training Needs Assessment Survey (TNAS) is a 40-question survey of perceived knowledge and skill in areas deemed critical to successfully navigating a new leadership position. Respondents are asked to indicate their current level of knowledge or skill on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = I have no knowledge/skills to 5 = I am highly knowledgeable/skilled). Responses on the TNAS provide insight into the skills and knowledge participants gained over time. The TNAS is administered online and takes approximately seven minutes to complete.

The Administrator Role Perception Survey

The Administrator Role Perception Survey (ARPS) is a 25-minute survey for center-based program administrators. Administrators complete the survey online and are later provided with an individual ARPS Profile. The ARPS Profile provides administrators with information about themselves as leaders. It identifies administrators’ developmental career stages based not on years of experience but rather on their perceptions of mastery of key early childhood program leadership competencies. The Profile incorporates the McCormick Center’s Whole Leadership Framework into the results, providing administrators with information on the amount of time they spend on administrative and pedagogical leadership functions as well as their strengths and areas for growth in each of the three, interdependent leadership areas. The three areas of the Whole Leadership Framework—leadership essentials, pedagogical leadership, and administrative leadership—reflect on everything the administrator, and often other staff members, do as early childhood program leaders.

Final Evaluation Survey

A final evaluation survey was administered online after the conclusion of the academy. Participants were asked to provide feedback regarding their experience with various components of the leadership academy, perceived areas of professional growth, and information regarding the role of the leadership academy in their professional journeys. Data from the final evaluations provided a reflection on the overall impact of the leadership academy and the identification of targeted areas for future improvement.

FINDINGS

Q1. Would it be possible for participants to focus on and prioritize their learning while also navigating personal and professional challenges?

The original design of the academy involved multiple, back-to-back days of in-person training. The adapted design shifted to remote learning sessions conducted by McCormick Center faculty in a seminar-like atmosphere over several months. Each participant received three books, a binder of handouts, a journal for self-reflection, and articles to guide their learning. Participants met virtually on a live platform from their home or work office for 16 half-days over four consecutive months. Additionally, training days were clustered by content over four months rather than scheduled for 16 sessions in a row. This scheduling allowed for deep immersion by topic with a continuous focus on overarching themes. The decision to use half-days clustered across months freed up portions of each training day to allow participants to still address their programs’ daily needs. Participants continued their learning in the interim between clustered sessions with required readings and brief assignments related to the topics discussed.

Providing a leadership academy that fosters a professional learning community inclusive of critical inquiry, a safe learning environment, and trusting relationships remained a high priority. This meant faculty needed to consider new ways to engage participants with both the faculty and each other. Faculty worked to construct a virtual environment where participants could feel the same level of comfort and appreciation as they would in an in-person classroom. This began with packing and mailing each participant a hospitality box—a box including learning materials (e.g., books, a journal for reflection, and learning resources) as well as fun and functional items that would typically be in a training room (e.g., pens and pencils, fidget toys, snacks, tea bags and instant coffee, notes of inspiration, etc.). The hospitality box was delivered to each participant at their preferred address, work or home, with the instructions not to open it until the first virtual session. At the first session, everyone opened their boxes together—a professional Big Reveal that set the tone for all sessions.

During sessions, participants were encouraged to share passions and struggles, activities were designed to allow for the co-construction of knowledge in Zoom breakout rooms, and time was set aside for participants to use their journals to reflect on assumptions and beliefs about their roles and the vital work they do. A special focus was placed on acquiring strategies to help prioritize work. Participants were encouraged to rethink their previous practices and implement methods of shared decision-making and leadership across their programs. Through follow-up assignments and resources, administrators were challenged to refine their practices, acquire new competencies, gain insights, and become more confident and effective leaders.

Overall, 81% of participants (9 out of 11) fully completed the academy, including the 48 hours of online learning and completion of the assessments for learning embedded within the three modules they selected from Aim4Excellence, a national online director credential. The two participants who did not complete the academy reported changes in their roles and responsibilities, as well as significant personal issues. This suggests that, despite the leadership academy redesign and radical hospitality efforts, outside forces still deeply impacted some participants’ capacities to fully engage in the professional learning experience.

Q2. Would participants value the knowledge and skills targeted in the academy?

The overall format of the academy encouraged a collegial atmosphere with formal presentations, large-group discussions, small Zoom breakout room activities, role-playing, opportunities for reflection, short assignments, and time to develop intentions and next steps. The scenarios and case studies used during the sessions were drawn from participant responses on pre-data collection measures. This allowed for the personalization of the curriculum content based on the unique program characteristics and themes that emerged from the data, which enhanced the applicability of this training, allowing us to make sure that the content felt relevant to the participants.

After the 16 remote learning sessions, which focused on leadership essentials, the participants utilized their pre-Administrator Role Perception Surveys (ARPS) Profile to guide them in individualizing a plan for the next phase of the academy by selecting three modules from Aim4Excellence to achieve competencies in either administrative leadership or pedagogical leadership. This choice provided participants with a sense of learning autonomy as they continued their leadership journey.

During this second phase of the academy, participants completed the three self-selected Aim4Excellence modules and engaged in a monthly facilitated online cohort (either a pedagogical leadership cohort or an administrative leadership cohort) for an additional three months. Designed as an engaging and interactive online professional learning experience, Aim4Excellence explores the core leadership competencies that early childhood program leaders need. The facilitation provided by faculty supported participants in completing the modules and applying new knowledge and skills in the participants’ respective centers. The facilitated cohort model for the Aim4Excellence modules provided the opportunity for continued peer learning and support built on the trust established during the first phase of the academy, Ready to Lead.

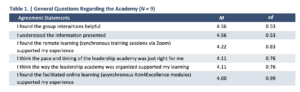

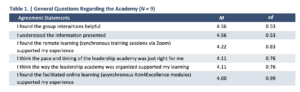

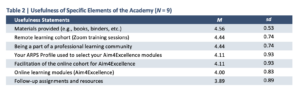

The Final Evaluation Survey provided answers to question 2. Overall, participants found the academy useful in their professional growth and challenging, especially in the face of ever-increasing personal and professional demands. On a scale of 1 = not at all to 5 = completely, participants were asked to rate the degree to which they agreed with some general questions regarding different components of the academy. Table 1 provides means and standard deviations for each statement.

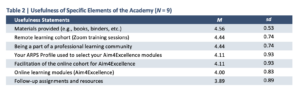

Next, participants were asked to rate how useful (on a scale of 1 = not at all to 5 = very) various elements of the Academy were and to share any additional information about their ratings. Results showed that all elements were perceived as useful, with materials provided having the highest rating and follow-up assignments and resources being the lowest. Means and standard deviations are provided in Table 2. Of particular interest were the participants’ ratings of the usefulness of the ARPS Profile to inform their choice of Aim4Excellence modules. Four participants rated it somewhat useful, three a bit useful, and five rated it very useful. Taken together, these ratings may suggest the need for additional professional development in interpreting and using individual ARPS Profiles to guide choices in leadership development.

Q3. Would the virtual academy be effective at improving knowledge and skills, levels of self-efficacy, and a sense of belonging to a professional community?

Formal data gathered from the TNAS, ARPS, and Final Evaluation allowed us to examine the impact of the academy on the desired learning and professional outcomes.

Training Needs Assessment Survey

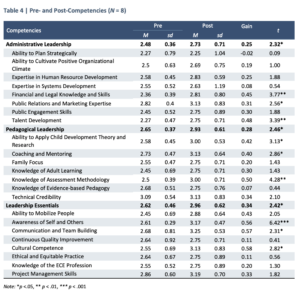

Paired t-tests were employed to explore changes in participants’ TNAS scores across time. The results of the data analyses revealed increases in all 40 areas and statistically significant increases in mean scores for 35 of the 40 areas assessed. Additionally, total TNAS scores showed a significant mean increase in knowledge and skill from pre (M = 103.44, sd = 23.55) to post (M = 161.89, sd = 19.69), t(8) = 6.56, p < .001. These results suggest that the training had a strong, measurable impact on participants’ level of knowledge and skill across a wide array of program leadership areas. Table 3 provides a summary of TNAS pre- and post-means and the results of the t-tests showing the improvements over time.

Administrator Role Perception Survey

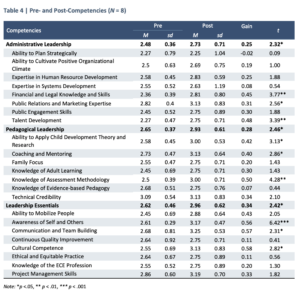

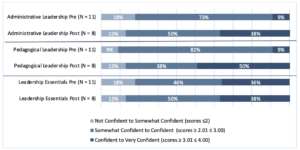

A total of 11 participants completed an ARPS prior to the start of the academy, and eight completed a post-ARPS upon completion of the Aim4Excellence modules. The results of the one-sample t-tests show that participants’ confidence significantly increased in all three Whole Leadership Framework domains, as well as in nine specific competencies. Table 4 shows the average scores and standard deviations for each competency (on a 4-point scale) pre- and post-training, the gain over time, and any statistically significant change from the beginning to the end of the training.

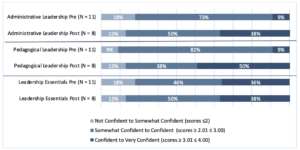

Moreover, comparisons of pre- and post-ARPS data suggest that the percentages of participants who felt Not Confident to Somewhat Confident in each of the three whole leadership domains before the training decreased while the percentages of participants who felt Confident to Very Confident in each of the whole leadership domains increased after the training. These gains in confidence are most notable in the domains self-selected by the participants: administrative leadership and pedagogical leadership. Figure 1 compares the frequencies of participant confidence levels before and after the academy.

Figure 1 | Confidence Ranges by Whole Leadership Domain Across Time

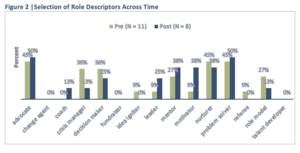

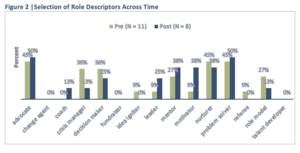

The ARPS also asks respondents to identify the three words that best describe their current role. We were interested in knowing if completion of the academy was associated with more favorable descriptions of the role of administrator. Results of pre- and post-comparisons showed a 13% increase in the selection of the word “coach”, a 16% increase in “leader”, an 11% increase in “mentor,” and a 29% increase in “motivator.” Results also showed a 23% decrease in the selection of “crisis manager” and a 9% decrease in “referee.” Interestingly, there was also an 11% decrease in the selection of “decision maker,” which likely reflects participants’ increased understanding and use of shared decision-making. These changes in role descriptors reflect a more positive portrayal of their administrative roles, selecting terms associated with effective and confident leadership and a positive work climate. Figure 2 shows changes in all words selected across time.

Final Evaluation Survey

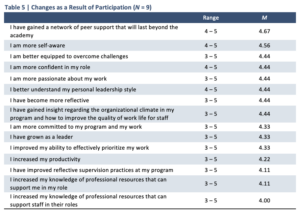

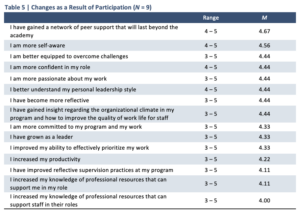

To learn more about increased internalization of leadership practices and improved program practices, we asked participants to rate, on a scale of 1 = not at all to 5 = completely, how much they agreed with statements regarding changes resulting from participation in the academy. All participants rated all statements positively, ranging from 3 = somewhat to 5 = quite a bit, indicating that the academy resulted in growth in all areas. Table 5 provides the ranges and means for each statement. Taken as a whole, the data suggests that the academy increased the number of administrators who internalized fundamental leadership practices, led to increases in administrators’ passion and commitment to the work and their programs, and improved program practices.

While the data collected to evaluate the academy were overwhelmingly positive and suggestive of the successful completion of the academy’s desired outcomes, a few notable areas for improvement and reflection were identified.

One specific area in which future leadership academies may seek to make changes is the outcome related to increasing program administrators’ access to resources to help them support the professional growth of their staff. While there was some evidence that participants benefited from specific resources and the use of their ARPS Profiles to support their own professional growth, the data also suggests that novice administrators need more learning and support for their role mentoring staff. Future leadership academies may need to consider adding curriculum items targeted toward building the capacity to seek out and find relevant professional resources.

When asked about suggestions for improvement to the academy, three themes emerged: no suggestions at this time (22%), additional information at the start of the academy regarding the time commitment (11%), and a desire to meet in person (44%).

DISCUSSION

This research brief offers a window into the changes made due to the pandemic to one of the McCormick Center’s traditional models of leadership development, the leadership academy. Further, it provides evaluation data from a fully remote (both synchronous and asynchronous) delivery model of a leadership academy, demonstrating many successful components and suggestions for improvements moving forward. Taken as a whole, the brief offers a springboard for future considerations on how to provide administrators with the targeted leadership development critical to the success of ECEC programs without compromising the elements we know to be vital in supporting learning and application of knowledge and skills.

While the pandemic significantly affected the ability of participants and faculty to travel and meet in person for this cohort of program leaders, the continuing staffing crisis makes a return to in-person professional development impractical in the near future. This study demonstrates that rigorous learning outcomes can be met via a fully virtual leadership academy. However, it is important to acknowledge that in-person learning is perceived by many participants as more desirable and has some distinct advantages for meeting the needs of adult learners (e.g., ease of creating a community of practice and engaging in effective small group activities). The long-term solution to the workforce crisis is not yet clear, but the need for flexible delivery models of coherent and intensive leadership development is well established.

The leadership academy—with time to reflect and apply new learning in a community of practice with peers—continues to be an effective and viable model of professional development for program administrators. Professional development entities must aim to deliver meaningful content that leads to mastery of competencies that impact professional practices. This high standard for professional development can be met through in-person, remote, or hybrid learning opportunities.

REFERENCES

Arabella Advisors. (2018). Developing early childhood leaders to support strong, equitable systems: A review of the early childhood education leadership development landscape. New Ventures Fund. https://www.arabellaadvisors.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/New-Venture-Fund_Packard_report_v7.pdf

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman and Co.

Bloom, P. J. (2016). Measuring work attitudes: Technical manual for the Early Childhood Job Satisfaction Survey and Early Childhood Work Environment Survey (3rd Ed.). Lake forest, IL: New Horizons.

Bloom, P. J. (1984). Self-efficacy expectations as a predictor of computer use: A look at early childhood administrators. Computers in the Schools 5(1/2), 45-63.

Bloom, P. J., & Abel, M. (2015). Expanding the lens: Leadership as an organizational asset. Young Children 70(2). https://www.naeyc.org/resources/pubs/yc/may2015/expanding-the-lens

Doherty, G., McCormick Ferguson, T., Ressler, G., & Lomotey, J. 2015. Enhancing child care quality by

director training and collegial mentoring. Early Childhood Research and Practice 17(1). http://ecrp.uiuc.edu/v17n1/doherty.html

Douglass, A. (2019). Leadership for quality early childhood education and care. Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD): Working Paper #211. http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=EDU/WKP(2019)19&docLanguage=En

Han, M., Buell, M., Hallam, R., & Hooper, A. (2021). An intensive professional development in family child care: A promising approach. International Journal of Early Years Education, DOI:10.1080/09669760.2021.1914558. http://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2021.1914558

Hashikawa, A., Sells, J., DeJonge, P., Alkon, A., Martin, E., & Shope, T. (2020). Child care in the time of coronavirus disease-19: A period of challenge and opportunity. Journal of Pediatrics. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7366077/

Masterson, M., Abel, M., Talan, T., & Bella, J. (2019). Building on whole leadership: Energizing and strengthening your early childhood program. Lewisville, NC: Gryphon House, Inc.

McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership (Summer 2020). Taking the Lead: Investing in family child care. Research Notes. Chicago, IL: National Louis University https://mccormickcenter.nl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/TakingTheLead_RN_RY_EDIT.pdf

McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership (Summer 2018). Director’s professional development needs differ by developmental stage. Research Notes. Chicago, IL: National Louis University. https://mccormickcenter.nl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ResearchNote_July2018.pdf

Sims, M., Forrest, R., Semann, A., & Slattery, C. (2015). “Conceptions of early childhood leadership: Driving new professionalism?” International Journal of Leadership in Education: Theory and Practice 18(2). http://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2014.962101

Talan, T., Bloom, P. J., & Kelton, R. (2014). Building the leadership capacity of early childhood directors: An evaluation of a leadership development model. Early Childhood Research and Practice. 16(1). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1045231.pdf