Current Role Perception, Job Satisfaction, and Confidence

A large body of research supports the theory that role perception, job satisfaction, and self-efficacy are important predictors of role commitment, job performance, and burnout (e.g., Khani & Mirzaee, 2015; Kotaro et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2021; Sandstrom et al., 2022; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2010; Spreitzer et al., 2005). The overarching findings from these studies suggest that when practitioners have favorable views of their professional role and a strong sense of competence in completing work-related tasks, they tend to be committed to their work and are better able to handle job-related challenges and stress.

Role Perception

Respondents were asked to select the three words or phrases that best described their role. Based on frequency, the top three choices for the full sample were educator (65%), family supporter (46%), and nurturer (37%). Role descriptors were further examined by years of FCC experience. Professionals with 0-5 years FCC experience were classified as novice professionals (n = 24), those with 6 – 15 years were classified as established professionals (n = 15), and 16 or more years were classified as seasoned professionals (n = 13). As demonstrated in Figure 7, over the course of their careers FCC professionals consistently referred to their work as educators and family supporters; however, across their years of experience, there appears to be an interesting evolution of the third descriptor representing increased identification as entrepreneurs and role models for established professional, and identification as advocates for seasoned professionals.

Figure 7

Role Descriptors by Years of Experience

Respondents were also asked to select the three words that best described their current job. For the full sample, the most frequent descriptor was rewarding (65%), followed by enjoyable (40%), and challenging (37%). Further analysis by experience found overlap with rewarding and enjoyable remaining stable across time, but that novice professionals most often selected challenging as their third descriptor, experienced professionals most often selected creative, and seasoned professionals most often selected exciting as their third descriptor (see Figure 8).

Role Congruence

Respondents were asked to rate on a Likert-scale how well elements of their work aligned with their ideals (0 = not at all like my ideal, to 5 = is my ideal). Figure 9 below shows the means for each comparison by element. Average congruence of how closely current conditions resembled their ideal was 3.37 (SD = 1.27) suggesting that overall, the role of the FCC professional is somewhat like the ideal. Figure 9 breaks down levels of congruence by specific elements of the role.

Critical Issues, Satisfactions, and Frustrations

Next, respondents were asked to select the three most critical issues they face running a FCC business. The most commonly selected issues were the demands of the job (47%), lack of benefits (44%), and difficulty recruiting and retaining qualified staff (33%).

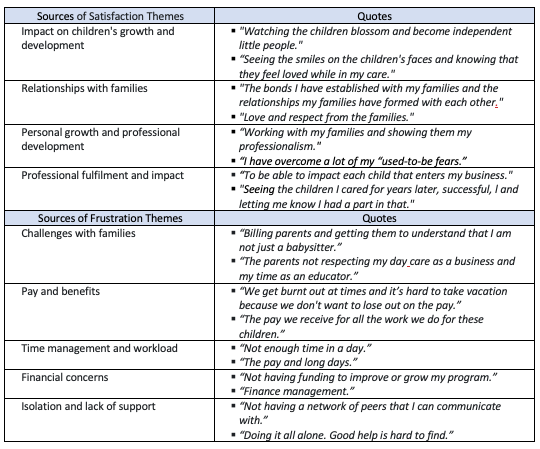

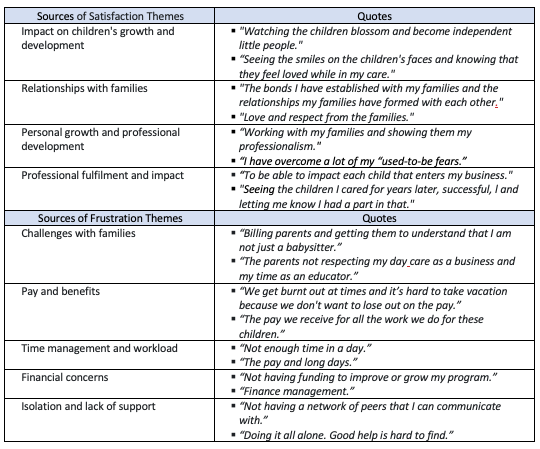

Respondents were also asked to describe the aspects of their work that brought them the greatest satisfaction and greatest frustration. Open-ended responses were then categorized into themes. As noted in Table 3, the top satisfaction themes revolved around relationships with children and families, positive impact on children’s lives, and personal and professional growth (e.g., overcoming challenges, worries, or fears).

Table 3

Satisfaction and Frustration Themes

Confidence in Competencies

Respondents ranked their current level of confidence across 38 competencies related to owning and operating a FCC business. Each question was scored on a four-point Likert scale (1 = I am not confident in my ability, 2 = I am somewhat confident in my ability, 3 = I am confident in my ability, 4 = I am very confident in my ability). The average score across all 38 competencies was 2.87 (SD = 0.66) and ranged from 1.24 to 4.00. Table 4 provides a breakdown of the five competencies in which FCC professionals expressed the highest level of confidence and the five competencies with the lowest level of confidence.

Table 4

Highest and Lowest Areas of Confidence

Role Commitment

The sample appeared to be strongly committed to their work. Eighty-one percent of respondents reported feeling very committed to their business, 88% reported taking pride in their business and 77% reported that they put a lot of extra effort into their work. Moreover, knowing what they know today about the satisfaction of their job, 96% would still become a FCC professional. However, the intention to stay in the role appears more nuanced with only 65% reporting they intend to run their program for at least two more years. Additionally, 14% reported that they often think about closing, and 8% reported that they sometimes feel trapped in their job. This may reflect FCC professionals desire for a career pathway that allows them to grow and advance in the field. This highlights a need for additional research on next steps for the FCC professionals after they close their programs.

DISCUSSION

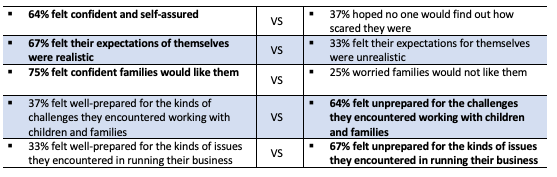

Research and reports focused on roles in ECEC serve as valuable resources for individuals considering a career in this field, as well as for educators, employers, policymakers, and other stakeholders interested in workforce development, talent management, and industry trends. They can inform decision-making processes related to education, training, recruitment, and workforce planning. This Research Brief provides a report of the regulated (licensed) segment of the FCC workforce. Data from a small, but relatively diverse sample of 52 FCC professionals suggest that they tend to enter the field feeling confident and self-assured. Despite their confidence; however, many felt unprepared for the challenges they face, especially in business-related areas. While 52% of the sample had no previous experience in ECEC, 46% did have prior teaching experience, yet only 15% had administrative experience. This diversity in backgrounds underscores the multidisciplinary nature of the FCC profession, with individuals entering from a range of educational and professional backgrounds.

The findings regarding the motivations for individuals to become FCC professionals provide valuable insights into the unique appeal and potential career pathways within the ECEC field. As illustrated in Figure 6, two primary motivations emerged as leading factors: the desire to be one’s own boss or run a business (23%) and the aspiration to be able to stay home with their own children (23%). These motivations reflect a distinct aspect of the FCC profession, highlighting the appeal of flexibility and autonomy that comes with operating a FCC program. The fact that only 10% of the sample were motivated by the encouragement of others presents an interesting contrast to data on center-based administrators, who often cite encouragement from others as a primary reason for entering their role (McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, 2018). More research is needed to further understand career motivations, but this discrepancy may suggest that FCC professionals are more often self-driven and motivated by intrinsic factors such as independence and the desire to balance work with family responsibilities.

A prominent discovery across the ECEC literature concerning leadership underscores the significance of individuals’ professional identity and their perception of themselves as leaders. Work in this area has highlighted the crucial role of self-efficacy, reflective practices, empowerment, and leadership purpose. This underscores the importance of measuring and supporting role-related factors when considering workforce well-being and sustainability.

Our findings reveal a consistent role-perception of FCC professionals as educators and family supporters across the span of their careers. However, an intriguing evolution is observed in experienced and seasoned FCC professionals that seems to extend beyond direct interactions with children and families. Mid-career professionals (with 6 – 15 years of FCC experience) appear to broaden their role identity to emphasize their work as small business owners and role models and seasoned professionals (16 or more years of experience) extend to include their role as advocates.

Interestingly, we found a similar evolution in how FCC professionals described their work. While rewarding and enjoyable remained consistent descriptors across time, new professionals most often selected challenging as a third descriptor, experienced professionals most often selected creative, and seasoned professionals most often selected exciting as their third descriptor. Additional research is needed but the shift may reflect a sense of resiliency and empowerment as professionals advance in their career.

This preliminary data begin to demonstrate how FCC professionals’ perceptions evolve across time. When new to the role, FCC professionals seem to emphasize their direct work with children and families, finding the work to be rewarding yet challenging. Mid-career FCC professionals’ role perceptions may expand to highlight their powerful role as small business owners embracing autonomy and creativity—the combination of being an entrepreneur and an educator is enticing for the mid-career FCC professional. Later in their career, the perception seems to extend past their influence within their individual programs to encompass the exciting role they play in advocating for and supporting the larger FCC and ECEC field.

The thematic analysis of the FCC professionals’ frustrations revealed several common themes including challenges in parent-provider relationships, time management and workload, financial concerns, and the need for staffing and support. Unsurprisingly, these areas overlap with the areas in which FCC professionals reported having the least confidence—the business and professional practices that foster a successful and sustainable business.

These findings also mirror previous research measuring FCC business and professional practices using the Business Administration Scale for Family Child Care (BAS) which found income and benefits, fiscal management, and provider as employer to be among the lowest rated items in a national sample of 210 FCC programs as well as a clear parallel to other research highlighting factors hypothesized to lead to professional burnout and program closure (e.g., Bromer et al., 2021; Kelton & Tenis, 2024; National Center on Early Childhood Quality Assurance, 2020; Vieria & Hill, 2019). Given the context of the sample’s educational background and work experience, these findings further elucidate the need for specialized training and coursework related to the business aspects of FCC. Addressing competencies in business and professional practice is crucial in improving the well-being and effectiveness of FCC professionals in delivering quality care to children and families.

This study provided nuanced results regarding the FCC professional’s commitment to the role. While the vast majority (85%) of the sample identified as very committed to their business, only 65% indicated that they plan to run their business for at least two more years. These data taken in conjunction with the role perception data raise interesting questions regarding the possibility that as their career advances, FCC professionals may look to close their programs but not necessarily leave the field. While there is a great deal of critical conversation around the alarming rates of FCC program closure, there is limited information about what FCC professionals do after closing their FCC businesses. Future research on FCC professionals should investigate if they move to other roles within the ECEC field, particularly if they obtain positions that allow them to support and advocate for FCC at the community or state level (e.g., with resource and referral agencies, unions, or FCC networks or associations).

While limited in sample size, the findings from this Research Brief underscore the multifaceted nature of the FCC profession, highlighting both its rewards and challenges. Areas of strength, such as dedication to children and families, are contrasted by areas needing greater support, particularly in business management and sustainability. These data also offer insight into the potential of individualizing professional development and support based on the FCC professional’s career stage. Specifically, highlighting the need to extend beyond education and caregiving practices to also encompass business and professional practices mid-career and to foster community and professional advocacy and leadership in more seasoned professionals. Addressing these needs and challenges, as well as delivering targeted professional development is crucial for the well-being, effectiveness, and retention of FCC professionals.

REFERENCES

Bella, J., Abel, M., Bloom, P.J., & Talan, T. (2017). Administrator Role Perception Survey. McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, National Louis University.

Bella, J., & Kelton, R. (2018). Administrator Role Perception Survey—Home-Based. McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, National Louis University.

Bipartisan Policy Center. (2021). Family child care policy framework. https://bipartisanpolicy.org/explainer/family-child-care-policy-framework/

Bloom, P. J. (2010). Measuring work attitudes in the early childhood setting: Technical manual for the Early Childhood Job Satisfaction Survey and the Early Childhood Work Environment Survey. McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, National Louis University.

Bromer, J., Porter, T., Jones, C., Ragonese-Barnes, M., & Orland, J. (2021). Quality in home-based child care: A review of selected literature. OPRE Report # 2021-136, Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/quality-home-based-child-care-review-selected-literature

Liu, D., Zhang, S., Wang, Y., & Yan, Y. (2021). The antecedents of thriving at work: A meta-analytic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1-20.

Khani R. & Mirzaee A. (2015). How do self-efficacy, contextual variables and stressors affect teacher burnout in an EFL context? Journal of Educational Psychology, 35(1), 93–109.

Kelton, R. & Tenis, I. (2024). Small business, big implications: A look at business practices in family child care programs. Research Notes. McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, National Louis University. https://mccormickcenter.nl.edu/library/research-note-240131/

Kotaro, S., Cieslak, R., Smoktunowicz, E., Rogala, A., Benight, C., & Luszczynska, A. (2015): Associations between job burnout and self-efficacy: A meta-analysis. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 1-20.

McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership (2018). Director’s professional development needs differ by developmental stage. Research Notes. National Louis University. https://mccormickcenter.nl.edu/library/directors-professional-development-needs-differ-by-developmental-stage/

National Center on Early Childhood Quality Assurance. (2020). Addressing the decline in family child care. Administration for Children and Families, Office of Child Care. https://childcareta.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/addressing_decreasing_fcc_providers_revised_march2020_final.pdf

Sandstorm, H., Casas, M., Hernadez-Lepe, F., & Greenberg, E. (2022). Early educators’ work experiences and job satisfaction: Findings from the District of Columbia child care policy research partnership. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2022-05/Early%20Educators%E2%80%99%20Work%20Experiences%20and%20Job%20Satisfaction.pdf

Skaalvik, E. M., Skaalvik, S. (2010). Teacher self-efficacy and teacher burnout: A study of relations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(4), 1059–1069.

Spreitzer, G., Sutcliffe, K., Dutton, J., Sonenshein, S., & Grant, A. M. (2005). A socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organization Science, 16(5), 537-549. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1050.0153

Vieira, N. & Hill. S. (2017). Creating the conditions for family child care to thrive. All Our Kin. https://allourkin.org/files/galleries/Family_Child_Care_to_Thrive.pdf