This document may be printed, photocopied, and disseminated freely with attribution. All content is the property of the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, there has been growing interest in the well-being, work stress, and coping strategies of the early childhood education and care (ECEC) workforce. Research has found that ECEC educators experience elevated rates of depression and stress compared to the general population (e.g., Brophy-Herb et al., 2023; Canobi et al., 2024; Kwon et al., 2019; Roberts et al., 2019). When adults’ well-being suffers, children’s well-being is likely affected as well. Teachers who experience stress and depression struggle to offer emotional support, model pro-social behavior, and effectively engage with students. They are also more likely to leave the profession (Jeon et al., 2014; 2018; Jepson & Forrest, 2006; Kwon et al., 2019; Whitebook et al., 2001).

While the focus on teacher well-being has increased, the experiences of ECEC center administrators remain largely unexamined. Administrators are critical to program quality. They serve as the linchpin for numerous functions that influence staff satisfaction and retention with responsibilities that include hiring and onboarding staff, supervising and promoting employees, managing finances, fostering a shared mission and vision, and shaping the overall organizational climate (Bloom & Abel, 2015; Doherty et al., 2015; Douglass, 2019; Douglass & Kirby, 2022; Sims et al., 2015; Kelton & Talan, 2023; Talan et al., 2014). Administrators also, directly and indirectly, affect teachers’ daily experiences, teaching practices, and job satisfaction and influence decisions to remain in their roles (Zinsser et al., 2016). Notably, Doromal and Markowitz (2023) surveyed 1,114 ECEC educators and found that perceptions of leader support were significantly associated with both teachers’ intentions to leave and actual turnover rates.

New or novice administrators in early ECEC settings typically have formal education and training in early education and child development but often lack preparation in program administration and leadership (Kelton & Talan, 2023; Kelton & Tenis, 2024; Talan et al., 2014). As a result, many struggle to navigate responsibilities in areas where they have little or no prior experience, such as human resources, coaching and supervision, program operations, strategic planning, and fiscal management (Kelton & Talan, 2023).

Decades of research in organizational psychology and human resources underscore the need for structured training and support for individuals transitioning into leadership roles. As Nick Taylor, CEO and co-founder of Unmind, aptly stated, “One minute, [managers] are praised for their individual contributions. Next, they are elevated into positions that can feel dramatically different from the ones they previously held. Then they’re left to decipher their way through the managerial maze without the additional support or development needed to succeed – or even to comprehend what their team actually needs from them.” This quote captures the challenges that many novice ECEC administrators face.

Better understanding administrators’ work experience is essential, given their pivotal role in program quality and teacher retention. Moreover, while formal data on administrator turnover is lacking, it is likely that administrators’ stress and well-being also affect their own retention. Despite the critical role administrators play in the sustainability of high-quality ECEC programs, empirical research on their unique experiences, needs, and challenges remains limited (Kelton & Tenis, 2024; Talan et al., 2014). This study seeks to understand the relationship between indicators of well-being, work-related positive and negative thoughts and emotions, and resignation considerations among novice administrators.

STUDY METHODOLOGY

Sample

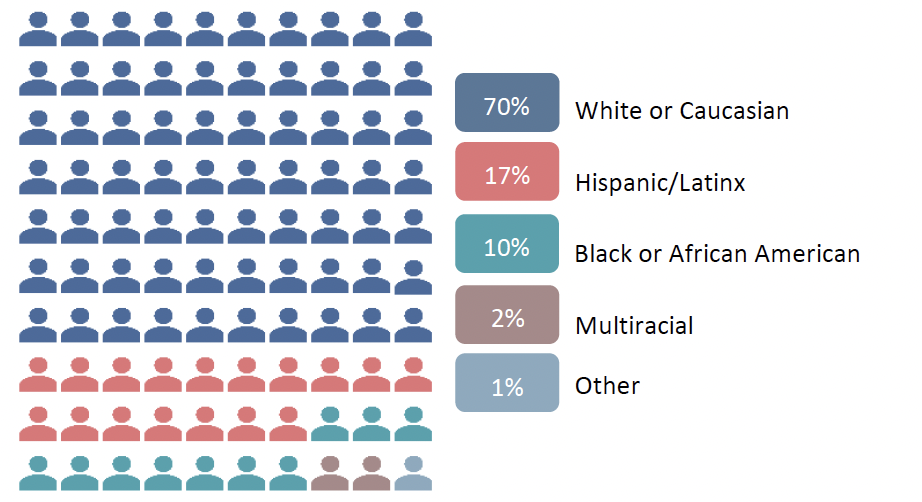

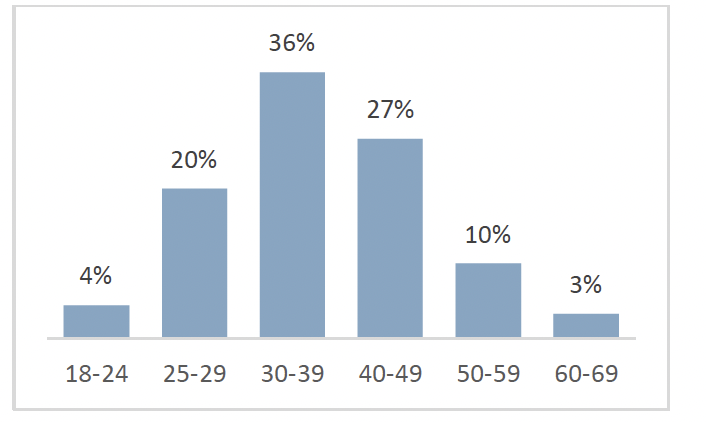

The sample included 90 center-based administrators. Data were collected as a part of a registration process for Ready to Lead, the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership’s 3-month-long leadership academy designed to support administrators who are new (within the first five years) to their administrative role. Forty-one percent of the sample identified their current role title as director, 38% as assistant director, 7% as executive director, 4% as coordinator, 4% as owner-director, 2% as manager, and 3% as other. Eighty-three percent indicated they shared their administrative responsibilities with at least one other person, and 22% indicated that their job description included regularly assigned classroom teaching. The sample predominantly identified as female (97%), 2% male, and 1% non-binary. The sample also represented a wide range of diverse races and ages (see Figures 1 and 2 below).

Figure 1

Participant Self-identified Race

Figure 2

Participant Age

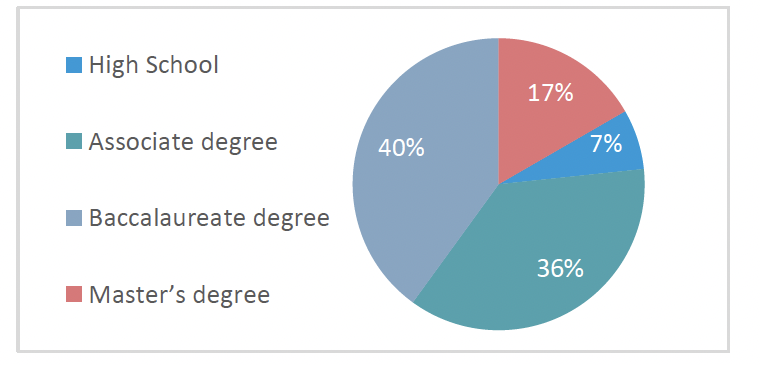

Experience in the field of ECEC ranged from 1 to 36 years, with an average of 13 (SD = 8.45) years of experience. Experience in current administrative position ranged from 0 to 5 years with an average of less than one and a half years (X = 1.36; SD = 1.43) and median of one year of experience (n = 89). The majority (93%) of the sample reported having a college degree. Figure 3 breaks down the degree by type. Of the six participants without a degree, three had previously taken college coursework in leadership, management, or program administration, and all six had taken college coursework in early childhood education or child development. Seventeen percent of the sample had a CDA, 33% (30) had a state or national administrator credential, 28% (26) had an early childhood teaching license or certificate, 10% (9) had an elementary teaching license or certificate, and 2% (2) had a principal endorsement.

Figure 3

Participant Highest Completed Level of Education

Total enrollment across the sample was 9,255 children and enrollment in individual programs ranged from 12 to 347 children. Average program enrollment was 102 children with a mode of 83. Eighty-eight percent (79) of the programs served infants, 92% (83) of the programs served toddlers, 97% (87) served preschoolers, and 57% (51) served school-age children. Ninety-seven percent (84) of the programs served a total of 4,910 children who had some portion of their child care cost covered by state subsidy. Twenty-one percent (20) of programs received Head Start or Early Head Start funding, and 16% (14) received Pre-K funding. Thirty-eight percent (34) of the programs were accredited.

Measures

Prior to the launch of each Ready to Lead cohort, participants are asked to complete a series of surveys, including an intake survey. Data for this study were pulled from the intake survey, which takes approximately 15 minutes to complete and includes participant and program demographic information and questions about the administrators’ previous professional experiences, subjective well-being, and commitment.

FINDINGS

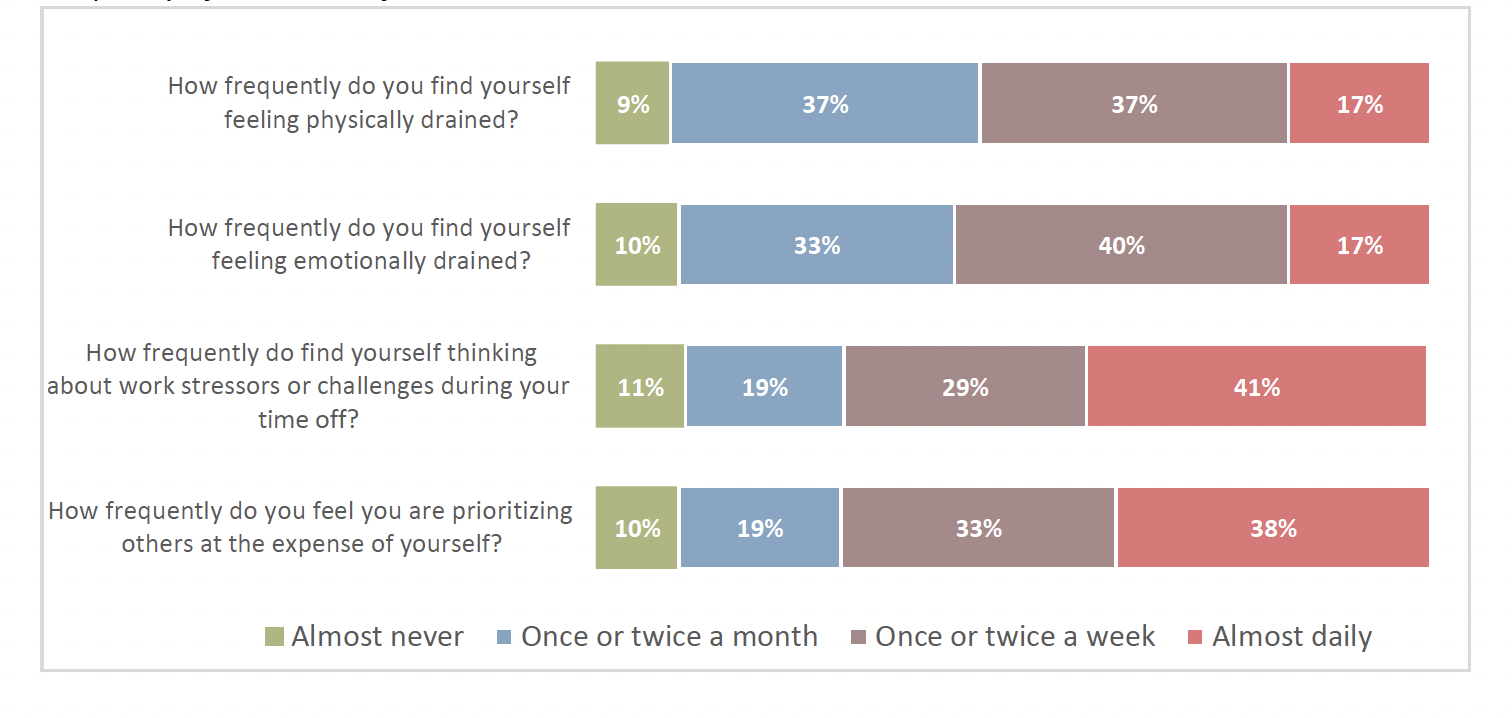

Indicators of Work-Related Stress and Burnout

Participants were asked to reflect on their current role and rate how frequently they experienced physical and emotional stress using a Likert scale (1 = almost never, 2 = once or twice a month, 3 = once or twice a week, 4 = almost daily). Administrators were also asked how often they experienced specific stress and burnout indicators using the same scale. The majority reported feeling physically (54%) or emotionally drained (57%) at least once a week. Additionally, 70% of the sample indicated thinking about work stressors or challenges during their time off at least once a week, and 71% reported prioritizing others at the expense of themselves with the same frequency. Figure 4 provides a detailed breakdown of responses for each question.

Figure 4

Frequency of Indicators of Work-related Stress and Burnout

Work-Related Thoughts and Emotions

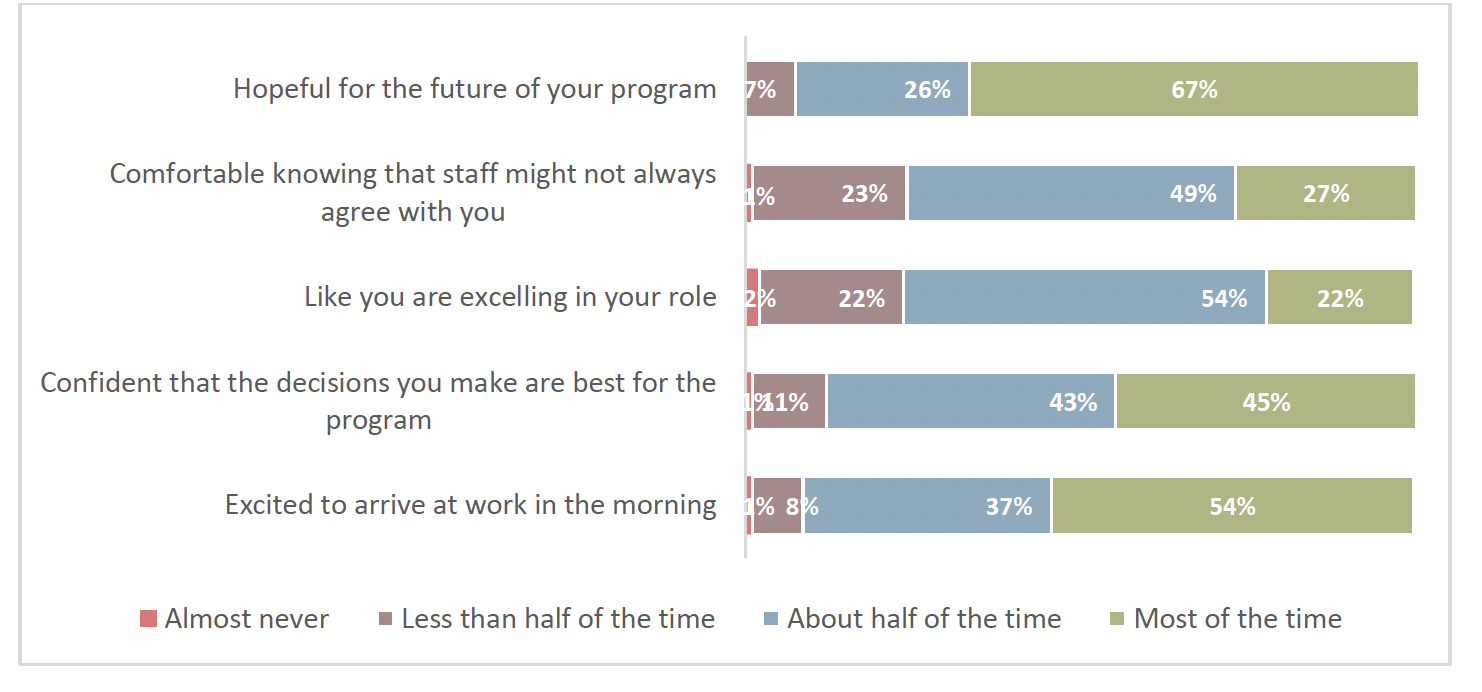

Next, administrators were asked how often they experienced both positive and negative thoughts and emotions about their work. The majority reported feeling hopeful about their programs at least half of the time (93%) and excited to arrive at work with the same frequency (91%). Additionally, 88% felt confident in their decisions at least half of the time, and 76% believed they were excelling in their role at least half of the time. Figure 5 provides a detailed breakdown of the frequency of positive thoughts and emotions.

Figure 5

Frequency of Positive Thoughts and Emotions

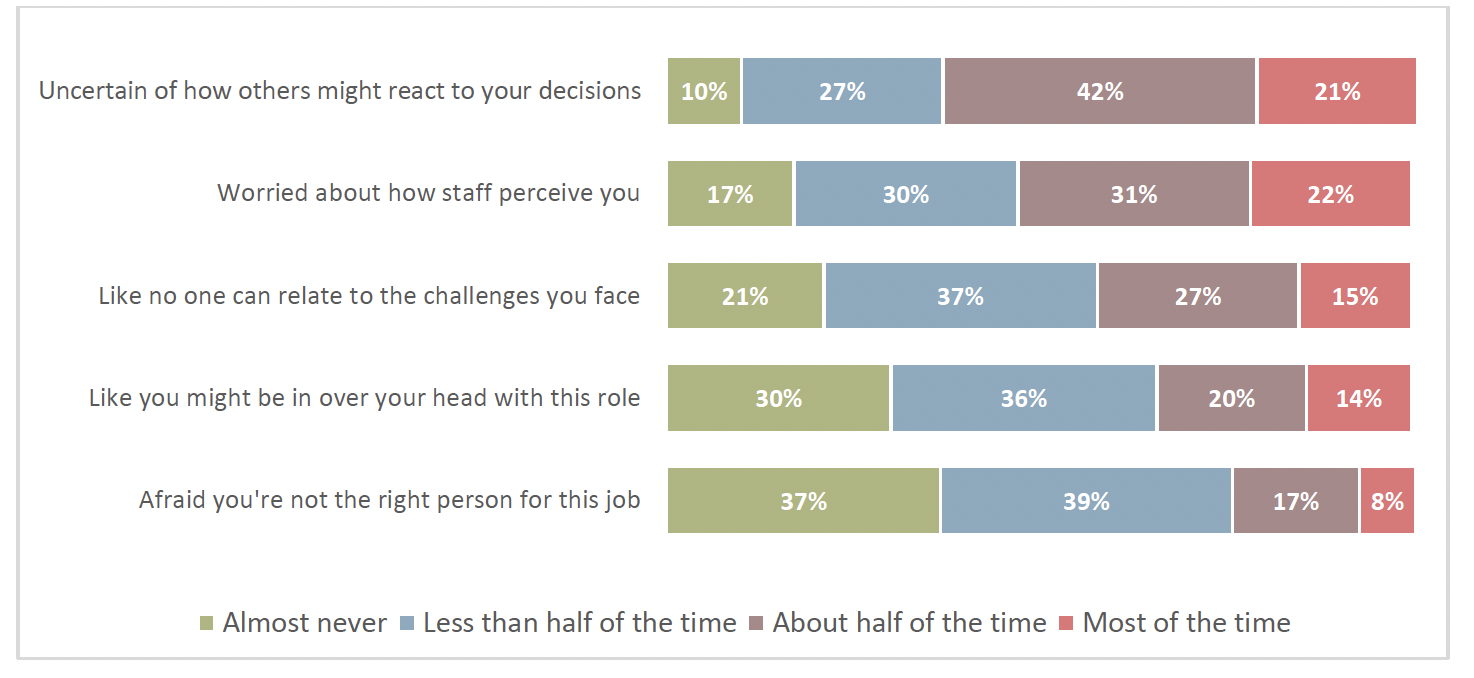

Regarding more negative thoughts and feelings, 63% of the sample indicated that at least half the time, they felt uncertain about others’ reactions to their decisions. The majority (53%) also worried about how their staff perceived them at least half of the time. Forty-two percent (42%) indicated that at least half of the time, they felt as though no one could relate to the challenges they faced. At least half of the time, 34% felt as though they were in over their head, and a quarter of the sample (25%) said they were afraid they were not the right person for the job. Figure 6 provides a more detailed breakdown.

Figure 6

Frequency of Negative Thoughts and Emotions

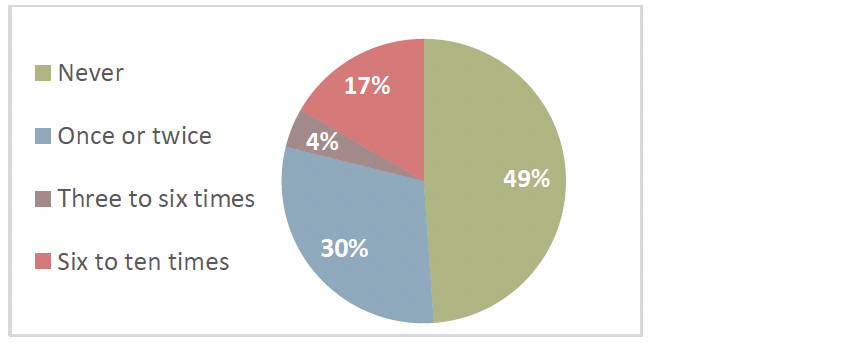

Commitment to Role and Field

We also examined novice administrators’ commitment to their current role, their dedication to the field, and the frequency with which they considered quitting. Overall, commitment appeared strong: 74% intended to stay in their current role for at least three more years, and 96% planned to remain in the field for at least that long. However, responses regarding thoughts of quitting were more nuanced. Nearly half (49%) of administrators reported never having considered quitting in the past six months. The remaining 51% had thought about quitting, with 30% considering it once or twice, 4% three to six times, and 17% six or more times during that period (see Figure 7).

Figure 7

Number of Times Administrators Considered Quitting During the Past Six Months

Relationship Between Workplace Stress, Positive and Negative Thoughts and Feelings, and Commitment

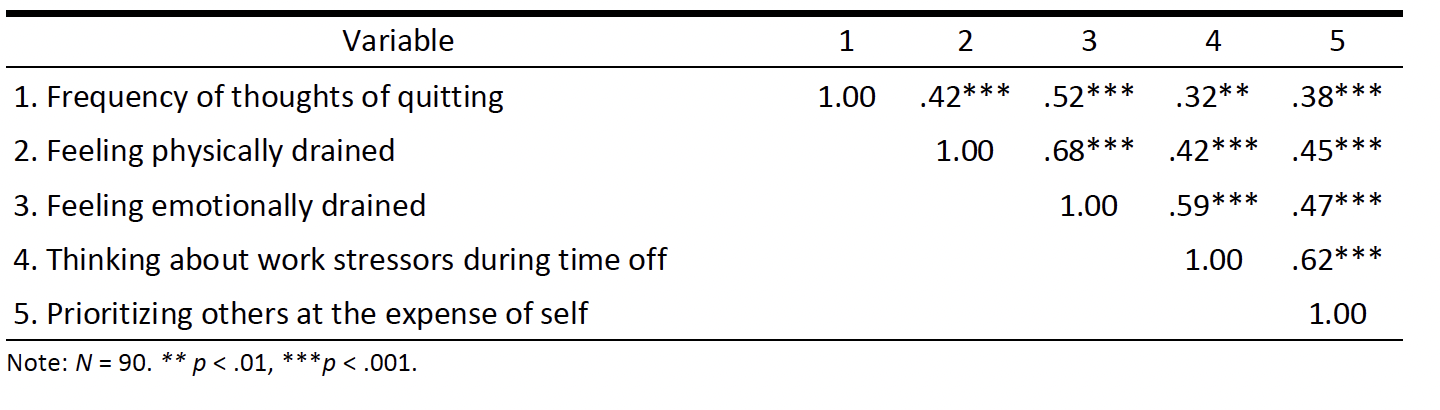

Spearman correlations were conducted to examine the relationship between administrators’ frequency of considering resignation and subjective indicators of stress, well-being, and work-related thoughts and emotions.

All correlations between workplace stress, poor well-being, and thoughts of quitting were positive and statistically significant (p < .001), indicating that as stress and well-being declined, thoughts of resignation increased (see Table 1). Among the measured variables, the frequency with which novice directors felt emotionally drained showed the strongest correlation with the frequency with which they thought of quitting (r = .52, p < .001). Table 1 below provides a detailed breakdown of all the correlations between workplace stress and well-being and thoughts of quitting.

Table 1

Correlations Between Thoughts of Quitting and Indicators of Workplace Stress and Well-being

The frequency with which novice administrators considered quitting was also significantly positively correlated with the frequency of negative feelings regarding their capabilities, concerns about staff perceptions, and a sense of isolation. Specifically, administrators who more frequently felt they were not the right person for the job (r = .37, p < .001) or felt they were in over their heads (r = .45, p < .05) reported thinking about quitting more often. Additionally, those who more frequently worried about staff perceptions (r = .22, p < .05) or felt uncertain about how others would react to their decisions (r = .27, p < .01) were likely to report thinking about quitting more often. A significant positive correlation was also found between feeling that no one could relate to their challenges and the frequency of thoughts of quitting (r = .31, p < .001).

Conversely, thoughts of quitting were significantly negatively correlated with excitement about work (r = -.28, p < .01) and hope for the program’s future (r = -.26, p < .001). While both correlations were weak, they suggest that the more positively administrators feel about their work, the less frequently they consider leaving.

DISCUSSION

Key Findings and Implications

This study supports the notion that novice administrators—those within their first five years in an administrative role—experience significant stress, uncertainty, and emotional strain. Specifically, this study found that:

Practical Implications and Future Directions

These findings highlight the urgent need for targeted support for novice ECEC administrators. Without adequate preparation and ongoing professional development, administrators may struggle with the demands of leadership, potentially leading to high turnover rates that further destabilize early childhood programs. Addressing these challenges could involve:

Future research should further explore the long-term impacts of stress and role strain on administrator retention and the effectiveness of targeted interventions in reducing turnover. Understanding how pre-service professional preparation, organizational supports, and in-service leadership development experiences influence job satisfaction could help create more sustainable career pathways for ECEC administrators.

REFERENCES

Bloom, P., & Abel, M. (2015). Expanding the Lens—Leadership as an Organizational Asset. YC: Young Children, 70, 10-17.

Brophy-Herb, H. E., Brincks, A., Cook, J. L., Stacks, A., Vallotton, C. D., Frosch, C., Carson, R., Wheeler, R., Perkins, H. A., & Jennings, P. A. (2023). Stress Intensity and Exhaustion Among Infant and Toddler Teachers: Descriptive Analysis and Associations with Sources of Stress and Coping Strategy Use. Early Education and Development, 34(7), 1545–1564.

Canobi, K. H., Eadie, P., Murray, L., Levickis, P., Page, J., & McFarland, L. (2024). Profiles of Professional Well-being and Turnover Intentions Among Australian Early Childhood Educators. Early Education and Development, 35(5), 1063–1079.

Doherty, G., Ferguson, T. M., Ressler, G., & Lomotey, J. (2015). Enhancing child care quality by director training and collegial mentoring. Early Childhood Research and Practice, 17(1).

Doromal, J. B., & Markowitz, A. J. (2023). Following the Leader: Associations between Leader Support and Teacher Retention in Child Care Settings. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 65, 250-260.

Douglass, A. (2019). Leadership for quality early childhood education and care. OECD Education Working Papers, N 211. OECD Publishing.

Douglass, A. &. Kirby, G. (2022). Evaluating leadership development in early care and education. OPRE Brief #2022-141. Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Jeon, H.-J., Kwon, K.-A., Walsh, B. A., Burnham, M. M., & Choi, Y.-J. (2018). Relations of early childhood education teachers’ depressive symptoms, job-related stress, and professional motivation to beliefs about children and teaching practices. Early Education and Development, 30(1), 131–144.

Jepson, E., & Forrest, S. (2006). Individual contributory factors in teacher stress: The role of achievement striving and occupational commitment. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(1), 183–197

Kelton, R., & Talan, T. N. (2023). We can’t afford to lose leaders: Professional development to increase administrator retention during the first few years. Research Notes. McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, National Louis University.

Kirby, G., Douglass, A., & Malone, L. (2023). Understanding and measuring leadership in center-based early care and education to inform policy and practice. OPRE Brief, #2023-177. Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Kwon, K.-A., Jeon, S., Jeon, L., & Castle, S. (2019). The role of teachers’ depressive symptoms in classroom quality and children’s developmental outcomes in Early Head Start programs. Learning and Individual Differences, 74.

Sims, M., Forrest, R., Semann, A., & Slattery, C. (2014). Conceptions of early childhood leadership: Driving new professionalism? International Journal of Leadership in Education, 18(2), 149–166.

Talan, T., N., Bloom, P. J, & Kelton, R. (2014). Building the leadership capacity of early childhood directors: An evaluation of a leadership development model. Early Childhood Research & Practice, 16.

Zinsser, K. M., Christensen, C. G., & Torres, L. (2016). She’s supporting them; who’s supporting her? Preschool center-level social-emotional supports and teacher well-being. Journal of School Psychology, 59, 55–66.

Whitebook M, Sakai L, Gerber E, Howes C. Then … now: Changes in child care staffing, 1994–2000. Technical report. Washington, DC: Center for the Child Care Workforce; 2001.