This document may be printed, photocopied, and disseminated freely with attribution. All content is the property of the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership.

The number of family child care (FCC) providers in the U.S. is declining at an alarming rate. From 2011 to 2017, there was a 35% decrease in FCC homes (National Center on Early Childhood Quality Assurance, 2019). A handful of advocates and systems leaders are responding to this trend by focusing their attention to understand the reasons for the decline and conducting research to explore solutions for its reversal (DiMatteo & Nzewi, 2019; Guzman, Hickman, Turner, & Gennetian, 2016; Hurley & Shen, 2016; Orfali & Tout, 2018; Porter & Reiman, 2016). Considering the substantial portion of child care that is represented in home-based child care (HBCC), a heightened level of concern is warranted and more research is needed.

One approach for supporting FCC providers is through staffed family child care networks (SFCCNs). Organizations such as child care resource and referral agencies (CCR&R), Head Start agencies (including Early Head Start and Migrant Head Start), child care organizations, shared services alliances, and social service agencies host SFCCNs. Through the network, paid staff members provide supports and services to improve program quality including technical assistance, training, coaching, and opportunities for peer support.

Juliet Bromer and Toni Porter recently published Mapping the Family Child Care Network Landscape: Findings from the National Study of Family Child Care Networks (2019). The report provides findings about the organizational characteristics, services offered to family child care providers, staffing and supervision, and evaluation/quality assessment of SFCCNs.

The National Study of Family Child Care Networks was a three-year exploratory study that included surveys, interviews with network directors, and in-depth case studies of two networks. The survey consisted of approximately 50 questions adapted from protocols developed previously by the authors. It was sent to 505 organizations that had potential to meet the study criteria. Of these, 275 responded and 156 were identified as SFCCNs that met the study criteria, located in 38 states and the District of Columbia. While the sample is broad, the authors reported it is not representative of all SFCCNs.

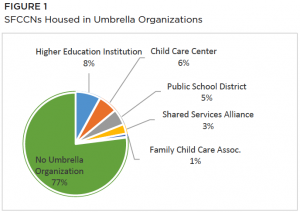

Of the types of organizations that sponsored SFCCNs, 42% were CCR&R organizations, 13% were from Early Head Start or Child Care Partnerships, and the remaining 44% were from other organizations. In addition, some SFCCNs were housed in larger umbrella organizations

including colleges and universities, child care centers, public school districts, shared service alliances, and family child care associations. Figure 1 shows the percentage of SFCCNs programs housed within larger umbrella organizations.

Qualitative interviews were conducted and analyzed with 46 SFCCNs and two unions. Eighteen of the 46 SFCCNs are highlighted as examples in the report. Profiles of these SFCCNs describe organizational characteristics, the FCC providers that they served, services offered, organizational staffing, and external evaluations.

The duration of SFCCNs was noteworthy, with nearly half (48%) reported having served HBCC providers (a broader term that includes FCC providers, but may also include family friend and neighbor care) for 20 or more years. Only 12% of the SFCCNs provided statewide services, while 42% served multiple counties and 46% served local communities. Forty-five percent of SFCCNs served urban providers with 28% serving FCC providers in suburban communities and 27% providing services in rural locations.

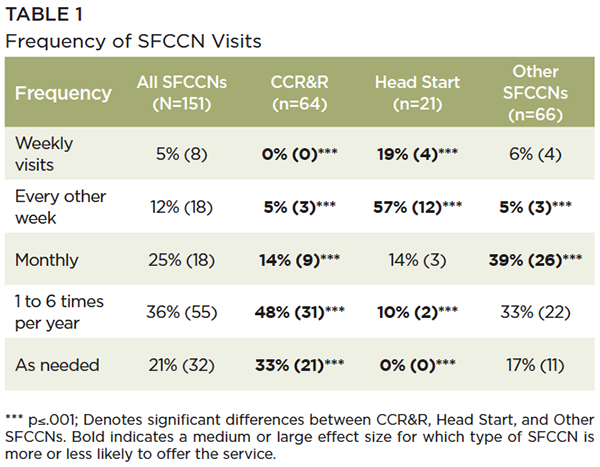

A majority (57%) of SFCCNs served 100 or less providers. However, these limited number of cases did not result in a high dosage of contacts. Nearly all (97%) SFCCNs reported that they made visits to provider homes, but only 17% visited more frequently than once per month, indicating a “light touch” approach. There were significant differences among CCR&Rs, Head Start SFCCNs, and other types of SFCCNs. Table 1 shows the frequency of visits and how they differ by program type.

Nearly all (97%) SFCCNs offered training to providers. More than 80% of SFCCNs report training on topics focused on early care and education. A majority also reported offering training related to managing a child care business (77%), licensing regulations (73%), stress management (73%), and working with dual language learners (59%). SFCCNs also offered opportunities for providers to learn from one another by sponsoring support groups and other activities including: staff and/or provider-facilitated peer support groups (73%), provider recognition events (53%), an annual conference (49%), peer mentoring (42%), and links to a family child care association (34%). CCR&R networks were closely connected to the quality rating and improvement systems (QRIS) in their states.

The survey examined the types of business and administrative supports offered by SFCCNs. The most frequently offered supports included: 1) developing policy handbooks and parent contracts and 2) helping to complete forms and applications. These were the only items that showed significant differences of magnitude among CCR&Rs, Head Start SFCCNs, and other types of SFCCNs. Table 2 shows the frequency of business and administrative supports offered and how they differ by program type.

Research suggests that a combination of services is more likely to support child care quality than single supports alone (Bromer, Van Haitsma, Daley, & Modigliani, 2009; Bromer & Korfmacher, 2017). The authors examined various combinations of services and found overwhelming evidence that Head Start SFCCNs combined services in contrast to CCR&R or other SRCCNs. Only SRCCNs associated with Head Start/Early Head Start offered a combination of services that predict quality. The percentage of Head Start SFCCNs providing various combined services included:

Family child care specialists, consultants, or coaches were the most common staff positions at SFCCNs. A majority of SFCCNs had staff that were dedicated to work with HBCC providers, but 60% reported that all of their staff worked with HBCC providers. As indicated in Figure 1, many SFCCNs are housed in larger umbrella organizations, which may account for the delegation of staff working with HBCC providers. Qualifications for staff working in SFCCNs mirrored that of child care center directors. Of SFCCN staff who work with HBCC providers, 52% were required to have a B.A. degree and 4% were required to have an M.A. degree.

We believe this report supports the notion that SFCCNs have the potential to increase the supply of FCC in local communities and should receive greater attention in early childhood systems development. These findings suggest that SFCCNs are embedded in a broad array of early childhood program support systems. They are found in a majority of states with approximately one-fourth associated with larger umbrella organizations. The longevity of SRCCNs serving HBCC providers suggests it is a sustainable model. However, the low dosage of site visits or “light touch” raises questions about the efficacy of the intervention for sustaining programs and improving quality. While a majority of SFCCNs offered a few business and administrative supports, there were additional supports to help with program viability that were not frequently offered. Expanding the array of services related to the administrative aspects of leading an FCC program may help to slow program closings. Future research is needed to examine the effects of SFCCNs in mitigating the decline in FCC supply through attrition.

These findings also suggest that SFCCNs are a promising approach to improve quality in FCC programs. The association between SFCCNs, CCR&Rs, and state QRIS suggest that the role of the network support specialist be included in state professional development systems. As with FCC provider sustainability, the impact of SFCCNs supports on FCC quality is directly related to the frequency of visits and the array of services provided. Therefore, policies and funding that support additional visits may be needed to achieve desired program outcomes.

The study highlights the need for additional support for SFCCN staff. The lack of standards for SFCCN staff members that serve HBCC providers is problematic for the credibility of these programs. Demonstrating competency of family child care network specialists, coaches, and mentors could raise the bar for the depth and intensity of the supports provided. Comparable qualifications and competencies in adult learning for SFCCN staff and center-based early childhood administrators should be examined.

Bromer, J., Van Haitsma, M., Daley, K., & Modigliani, K. (2009). Staffed support networks and quality in family child care: Findings from the Family Child Care Network Impact Study. Chicago, IL: Herr Research Center for Children and Social Policy, Erikson Institute. Retrieved from: https://www.erikson.edu/wp-content/uploads/fccnetwork_execsummary1.pdf

Bromer, J. & Korfmacher, J. (2017). Providing high quality support services to home-based child care: A conceptual model and literature review. Early Education and Development, 28(6), 745-772.

Bromer, J., & Porter, T. (2019). Mapping the family child care network landscape: Findings from the National Study of Family Child Care Networks. Chicago, IL: Herr Research Center, Erikson Institute.

DiMatteo, G. & Nzewi, K. (2019, February 20). Decline of family child care. [Presentation]. California Child Care Resource and Referral Network.

Guzman, L., Hickman, S., Turner, K., & Gennetian, L. (2016). Hispanic children’s participation in early care and education: Parents’ perceptions of child care arrangements, and relatives’ availability to provide care. MD: The National Center for Research on Hispanic Families & Children.

Hurley, K. & Shen, J. Z. (2016). Bringing it all home: Problems and possibilities facing New York City’s family child care. Center for New York City Affairs.

National Center on Early Childhood Quality Assurance (April 25, 2019). Strategies to strengthen family child care: Addressing the decreasing number of FCC providers. [Presentation] Unpublished data analysis. Retrieved from: https://childcareta.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/public/190424_fcc_webinar_2.pdf

Orfali, N. & Tout, K. (2018). Using administrative data to understand the decline of family child care. [Presentation]. Office of Child Care, State and Territory CCDF Administrators Meeting, Arlington, VA.

Porter, T., & Reiman, K. (2016). Examining quality in family child care: An evaluation of All Our Kin. New Haven, CT: All Our Kin. Retrieved from: http://www.allourkin.org/sites/default/files/ExaminingQualityinFCC2016.pdf