This document may be printed, photocopied, and disseminated freely with attribution. All content is the property of the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership.

This resource is part of our Research Notes series.

An important function of administrators seeking to improve program quality is to ensure that staff have access to a range of professional development (PD) opportunities. The director’s role in supporting access to PD involves much more than sharing information about training opportunities.1 It includes providing access to resources, setting aside planning time, providing career guidance, and establishing a career ladders within the program.

While there is wide consensus about the importance of professional development, there is a lack of research on the specific ways early childhood programs implement it. To address this issue, the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership recently conducted an online survey to explore the type and usefulness of various professional development opportunities in center-based early childhood programs.

Participants were solicited from approximately 29,000 constituents of the McCormick Center’s database. Information about the participants and their programs was collected. Of the 576 respondents, 71% served in an administrative capacity (director, assistant director, or component coordinator) and 29% were teachers. Three-fourths of the sample held a bachelor’s degree or higher. On average they had worked in the field for 20 years, with an average of 11 years at their current employer. They represented programs in 44 states, the District of Columbia, and American Samoa.

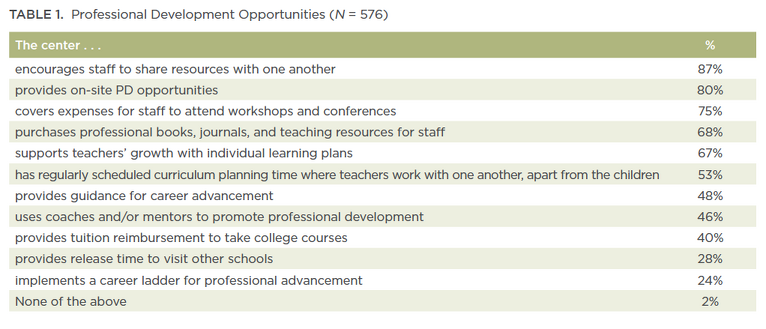

The online survey was designed to assess the frequency of 11 professional development supports found in center-based programs. It also assessed whether PD supports strengthened respondent’s level of professional competence, their perceptions about the importance of professional development activities, and their level of commitment to their current job.

Findings indicated that most center-based programs offered some professional development supports, but did not provide a comprehensive PD program. Of the 11 types of PD supports, the average number offered in centers was 6.15 (SD = 2.69).

A majority of programs provided digital and print resources, on-site professional development, and scheduled curriculum planning time. They also paid for off-site professional development and utilized individual learning plans. However, more than half of respondents’ programs did not support their staff with career guidance, coaches/mentors, or offer tuition reimbursement for college coursework. Only one-fourth of programs offered release time to visit other schools or had a career ladder in place. Table 1 shows the percentage of professional development supports offered by programs in rank order.

Less than one-half of respondents (43%) felt that the professional development opportunities provided in their programs were very helpful in strengthening their level of professional competence. However, a high percentage of respondents (82%) felt that taking part in professional development activities was still very important. Three-fourths of the participants (77%) stated that they were very committed to their current job.

Centers with differing program characteristics were compared to determine if they predicted the frequency of PD supports available in centers. One-way analysis of variance procedures were performed to assess how PD opportunities differed based on center size, program type, funding source, accreditation status, and participation in a state quality rating and improvement system (QRIS).

Significant differences were found based on program size for the following four PD supports:

Provides on-site PD F(3,544) = 17.00, p < .001

Uses coaches or mentors F(3,544) = 6.92, p < .001

Provides tuition reimbursement F(3,544) = 4.07, p < .01

Supports individual learning plans F(3,544) = 3.16, p < .05

Eight PD supports were found to be statistically significant when comparing centers that were NAEYC accredited to those that were not accredited:

Implements a career ladder F(1,513) = 16.42, p < .001

Provides tuition reimbursement F(1,513) = 14.13, p < .001

Uses coaches or mentors F(1,513) = 14.11, p < .001

Schedules curriculum planning time F(1,513) = 10.74, p < .01

Provides career guidance F(1,513) = 9.79, p < .01

Provides on-site PD F(1,513) = 9.73, p < .01

Supports individual learning plans F(1,513) = 9.05, p < .01

Covers expenses to attend workshops and conferences F(1,513) = 8.56, p < .01

No significant differences were found between programs that participated in state QRIS from those that did not.

The findings of this study suggest that early childhood administrators and teachers alike believe that professional development is important and that it is a pathway to strengthening professional competence. They also indicate that many programs are addressing access to professional development for their staff, yet a more comprehensive approach may be needed in order to provide the kind of support that will increase workforce capacity.

With a mandate from the Institute of Medicine report: Transforming the workforce for children birth through age 8: A unifying foundation2 that lead educators have a minimum of a bachelor’s degree, the finding that 60% of early childhood programs do not provide tuition reimbursement for college coursework is problematic. Furthermore, these findings suggest that most center-based administrators failed to provide the kinds of supports that will help their employees advance their careers and develop long-term increased professional competence over time such as guidance for career advancement, providing coaching and mentoring, and establishing an internal career ladder.

Differences found among programs of varying sizes suggest that policy and systems developers may need to consider a differentiated approach to PD initiatives. If smaller programs lack the capacity to offer on-site PD or provide coaching to classrooms teachers, they may need additional resources over larger programs. Similarly, limited program capacity may explain differences found regarding the provision of tuition reimbursements and individualized learning plans. Multiple solutions may be necessary to address the complexity of access to PD in early childhood. Increasing access to workforce supports—such as T.E.A.C.H. scholarships—may benefit smaller programs that lack the capacity to offer tuition reimbursement on their own.

The significant differences found between programs that were NAEYC accredited and those that were not suggest high quality program and professional standards may be a driver for the availability of comprehensive professional development opportunities. Accredited programs were found to be different from non-accredited centers in that they offered eight of the eleven PD supports. While each individual PD support is likely to benefit staff, the cumulative impact of an array of PD supports offered in accredited programs may have the greatest potential to increase workforce capacity.

Additional research is needed to further explore the accessibility of comprehensive PD supports in early childhood centers. This study was limited in several ways which should be considered in making conclusions. The survey was conducted with constituents of the McCormick Center and relied on self-reported data. Although all the group sizes examined in the ANOVA analyses were large, violations of the homogeneity of variance assumptions were found. Additional research to examine larger samples would improve generalizability.