This document may be printed, photocopied, and disseminated freely with attribution. All content is the property of the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership.

BACKGROUND

Given the current context of a pandemic, social and economic upheaval, and the pressing challenge of structural racism, research to advance the profession of early childhood education and care (ECEC) leadership is of critical importance. The current crises have exacerbated long-standing challenges, such as a lack of coordinated policy, disparate regulations, and fragmented funding (Bassok, Magnuson, & Weiland, 2016). With substantial variation in the quality and availability of ECEC, under-resourced communities remain without the structural and economic support to stabilize services and thrive (Hasikawa, Sells, DeJonge, Alkon, Martin, & Shope, 2020; Malik, Hamm, Schochet, Novoa, Workman, & Jessen-Howard, 2018).

As gatekeepers to quality, ECEC program leaders have a direct impact on organizational climate, teaching practices, and family engagement in their programs (Bloom & Abel, 2015; Douglass, 2019). There has been little research, however, on the diversity of ECEC program leaders. School leaders are predominantly white, with only 20% of public school principals representing individuals of color (USDOE, 2016). In the child care sector, about 40% of the early childhood workforce and 52% of those working with infants and toddlers are women of color, with low wages and scarce opportunities functioning as barriers to advancement (McLean, Austin, Whitebook, & Olson, 2021; NAEYC, 2019). These findings call for an imperative to include the voices of leaders of color in exploring pathways to racial equity and conversations related to the direction of the ECEC profession (Robinson, 2020). There is a critical need to examine and dismantle structural racism and to create an equitable system of inclusion for ECEC program leadership.

The Leading with Equity: Building Leaders research project addresses a gap in the existing research by explicitly addressing social justice, diversity, equity, and inclusion in the context of ECEC program leadership structures, systems, and practices. It explores how early childhood leaders of color perceive their input into the formation of professional competencies, professional development policy, and the future direction of the ECEC leadership profession.

This brief is concerned with just one of the research questions guiding the Leading with Equity research project: How has race, culture, or language influenced the leadership journeys of ECEC program leaders of color?

METHODS

Data were collected through 13 semi-structured, virtual focus groups (one was conducted in Spanish with translation provided); each group moderated by two early childhood researchers, one Black and one white. A professional speech-to-text service (Rev.com) transcribed the video recordings.

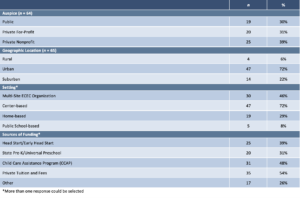

The sample was comprised of 65 program leaders of color from 18 states and the District of Columbia (with 51% from Illinois). Figure 1 illustrates the geographic distribution of the program leaders in the sample. The ECEC programs led by study participants varied by setting, sector, and funding streams. Programs were located in centers (72%), homes (29%), and public schools (8%). About 70% of the programs represented provided Head Start/Early Head Start or state-funded Pre-K. Table 1 provides the complete program characteristics.

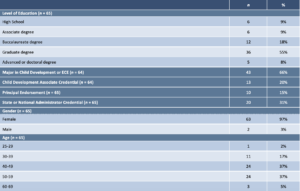

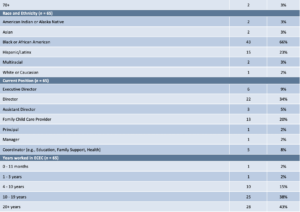

By design the participants were racially and culturally diverse: two-thirds (66%) of the participants identified as Black or African American, 23% identified as Hispanic or Latinx, 3% identified as American Indian or Alaska Native, 3% identified as Asian, 3% identified as Multiracial, and 2% identified as White or Caucasian (one participant was an English learner immigrant from Turkey). Table 2 provides the participant characteristics.

Four researchers coded the data with assistance in defining the coding themes from a national expert on early childhood leadership who is also the project’s principal investigator. Overall, the coding team has strong background knowledge in early childhood leadership and qualitative analysis, and is racially and culturally diverse. The researchers used an open-coding method to develop themes based on the first three focus groups transcriptions; codes were further refined and expanded as the coding progressed. The meaning of the data was negotiated until consensus amongst all coders was reached.

Data analysis involved the identification, examination, and interpretation of themes that emerged in the transcribed textual data. NVIVO 12, a qualitative analysis software, was utilized to process the data.

FINDINGS

When did you first think of yourself as an early childhood education and care leader?

Three responses were given most frequently:

Other pathways to becoming an ECEC leader included being a passionate teacher or having certain innate traits. I was born a leader.

How has race, culture, or language influenced your leadership journey?

The responses to this question have three themes: (1) empowering; (2) constraining; and (3) both empowering and constraining. Overall, the race, culture, or language of participants was more likely to have constrained than empowered their leadership journeys. A substantial number of respondents indicated that race, culture, or language was both constraining and empowering. Only one participant thought there was no impact on her leadership journey.

Working with diverse families

Representing children and families from their own or other under-represented groups

Decision makers are predominantly white

Gatekeepers prevent people of color from advancing

Distrust of leaders of color even when in the position of authority

Stereotypes in workplaces based on race, gender, language, and role

Language barriers for leaders who are English learners

Self-reflection. A frequently coded response was that self-awareness built confidence and self-efficacy.

Advocacy. The most frequently coded response (40% of responses in the Both Empowering and Constraining category) was that their own negative experiences empowered them to advocate for staff, self, children, families, and the early childhood education profession.

Proactive Approach. Some leaders adopted proactive approaches to overcoming constraints experienced due to their racial, cultural, or linguistic background, including advancing their education beyond what was required, seeking mentorship from others, opening communication to address potential biases, and extending themselves beyond the norm to build partnerships with others.

DISCUSSION

While not surprising that people of color report that race, culture, or language had a constraining impact on their leadership journeys, it is notable that approximately half of the responses from program leaders indicate that race, culture, or language had both a constraining and an empowering impact on their professional journeys. These program leaders reported being able to shift their perspectives from constrained to empowered primarily through demonstrating self-awareness or advocacy, both of which are core early childhood leadership competencies. These findings suggest the need for more research on the strengths and assets, as well as challenges, facing diverse ECEC program leaders. Additionally, professional development and degree programs that prepare ECEC program administrators should offer content to build competencies in personal and professional self-awareness as well as leadership and advocacy.

Figure 1. States Represented in Sample

Table 1. Program Characteristics

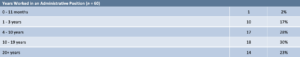

Table 2. Participant Characteristics

REFERENCES

Bassok, D., Magnuson, K., & Weiland, C. (2016). Building a cohesive, high-quality early childhood system. In M. Hansen & J. Valant (Eds.), Memos to the President on the Future of U.S. Education Policy. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Bloom, P. J., & Abel, M. (2015). Expanding the lens: Leadership as an organizational asset. Young Children 70(2). https://www.naeyc.org/resources/pubs/yc/may2015/expanding-the-lens

Douglass, A. (2019). Leadership for quality early childhood education and care. Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD): Working Paper #211. http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=EDU/WKP(2019)19&docLanguage=En

Hashikawa, A., Sells, J., DeJonge, P., Alkon, A., Martin, E., & Shope, T. (2020). Child care in the time of coronavirus disease-19: A period of challenge and opportunity. Journal of Pediatrics. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7366077/

Malik, R., Hamm, K., Schochet, L., Novoa, C., Workman, S., & Jessen-Howard, S. (2018). America’s child care deserts in 2018. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/americas-child-care-deserts-2018

McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership. (2020 Fall). Stronger together: A call for a unified framework for onsite leaders of early learning programs. Research Notes. Chicago, IL: National Louis University. https://mccormickcenter.nl.edu/library/stronger-together/

McLean, C., Austin, L.J.E., Whitebook, M., & Olson, K.L. (2021). Early Childhood Workforce Index – 2020. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://cscce.berkeley.edu/workforce-index-2020/.

National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC). (2019). Leading with equity: Early childhood educators make it personal. Summary of the Leading and Working Toward Equity Leadership Summit. Washington, D.C.: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Robinson, A. (2020). Reflections and Recommendations from Interviews with Eight Early Childhood Education Policy Leaders of Color: Why is Everyone at the Policy Tables So White? University of Maryland. https://spp.umd.edu/sites/default/files/2020-04/Reflections%20and%20Recommendations_4-27%20Final.pdf

U.S. Department of Education. (2016). The state of racial diversity in the educator workforce. Washington, D.C.: Policy and Program Studies Service Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development, U.S. Department of Education. https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/highered/racial-diversity/state-racial-diversity-workforce.pdf\