This document may be printed, photocopied, and disseminated freely with attribution. All content is the property of the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership.

Effective leadership is key to organizational health and to the delivery of high quality services. While there is a substantial body of research studying the impact of leadership on positive outcomes in business, health care, and K-12 education, the literature is less robust in regard to early childhood education. However, the significance of ECE program leadership as a driver of quality outcomes for children, families, and staff is now emerging (Kirby et al., 2021; Douglass, 2017; Bloom & Abel, 2015; Talan et al., 2014). The competencies to foster the organizational conditions that attract and retain teachers are understood to be multi-dimensional and relate to distributed leadership, shared decision making, supervisor and peer support, job-embedded learning, and an equitable reward system (Bloom, 2016; Joo et al., 2020; Lee & Louis, 2019).

Over the course of three years, the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership at National Louis University provided quality supports for 34 rural child care centers participating in the ExceleRate Child Care Pilot funded by Illinois’ Preschool Development Grant, Birth to Five.* The overarching goal of the pilot was to test new strategies to strengthen the effectiveness of child care programs by a) use of child care contracts providing funding for additional classroom staff and an enhanced salary scale based on the education and credentials of staff and b) leadership supports to establish continuous quality improvement (CQI) systems at the classroom and organizational levels. These supports included creating new structures to support CQI (Plan Do Review meetings; Individual Leadership Development Plans), implementing new processes (shared decision making; leadership coaching; Community of Practice), and supporting the professional growth of staff (new model of job-embedded leadership development). This study focused on the effectiveness of the quality supports component of the ExceleRate Child Care Pilot.

PILOT ACTIVITIES

During the first year of the pilot, reliable assessors provided classroom quality support through formal Environment Rating Scale (ERS) assessments with direct feedback and coaching for teaching staff in two classrooms within each center. The ERS data informed monthly Plan Do Review meetings throughout the pilot, during which classroom staff worked with administrators to strengthen teaching practices.

Also in the first year, all staff were invited to participate in an organizational climate assessment, the Early Childhood Work Environment Survey (ECWES), and each administrator completed an Administrator Role Perception Survey (ARPS). An individual ARPS Profile was provided to each administrator as well as an ECWES Profile of the organizational climate at their center. These data informed the development of an Individual Leadership Development Plan (ILDP). A Leadership Coach provided supports for CQI through monthly coaching sessions with program administrators, the development of the ILDP, a facilitated Community of Practice (CoP), and job-embedded leadership development to support the achievement of five Illinois Director Credential competencies (from two of the Administrative Content Areas of the IDC: Leadership and Advocacy and Personal and Professional Self-Awareness).

SAMPLE

All Illinois licensed centers located in Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP) Group 2 (rural) counties were eligible to participate in the ExceleRate Pilot if they served at least 40% CCAP children. Thirty-four out of fifty programs opted in. 100% of participants were white or Caucasian. At the beginning of the pilot, 43% of administrators had been in their role for 0-5 years, 11% had been in their role for 6-10 years, 27% had been in their role for 11-20 years, and 19% had been in their role for 20+ years. 79% of the centers were for-profit, and 21% were not-for-profit. At the beginning of the pilot, 38% of the centers were at the Gold Circle of Quality in ExceleRate Illinois, the Quality Rating and Improvement System; 26% were at the Silver Circle of Quality, and 35% were at the licensed level. Additionally, 9% of centers were NAEYC accredited, 21% were NAC accredited, and 3% were COA accredited.

Data were collected from the directors and staff of 31 rural center-based child care programs that participated throughout the three-year pilot. This study highlights the key findings from the evaluation of the quality supports component of the pilot. Pre and post analyses of the organizational climate assessments as well as administrators’ evaluations of the pilot were used to evaluate effectiveness.

MEASURES

Early Childhood Work Environment Survey (ECWES). The ECWES was employed to measure the organizational climate of the ECE program across ten dimensions (subscales) and staff’s commitment to the organization. The ECWES was administered at the beginning and at the conclusion of the ExceleRate Pilot (Bloom, 2016). Pre and post ECWES data representing 498 (pre) and 519 (post) staff across 31 programs were used for the analysis, and paired ttests were used to examine changes across time.

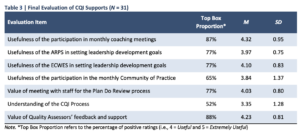

Finale Evaluation. Administrators were also asked to provide feedback on the effectiveness of the quality supports components of the pilot upon completion of the three-year grant. Thirty-one participants provided responses to the evaluation. The 5-point scale (from 1 = Not at all Useful to 5 = Extremely Useful) was used.Top Box Proportion (positive responses of 4 = Useful and 5 = Very Useful) was used for quantitative analysis. The open-ended responses were summarized for qualitative findings.

FINDINGS

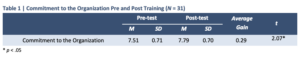

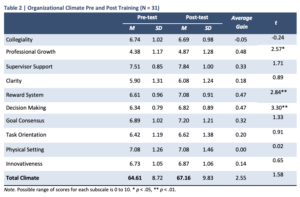

The data revealed some compelling information about the impact of the pilot at both the programmatic and individual levels and suggested areas of additional support. Table 1 shows the average scores and standard deviations for commitment to the organization. Table 2 provides the means and standard deviations for each of the ten dimensions of organizational climate (possible range of scores for each subscale is 0 to 10). Table 3 provides means, standard deviations, and percentage of the positive comments for each of the pilot’s components. Key findings in each area are noted below.

Center-Level Improvements

Individual Growth

Further Support Needed

DISCUSSION

Encouraging professional growth and improving the reward system were built into the ExceleRate Pilot’s objectives and deliverables. Seeing a significant increase in these dimensions of organizational climate as measured by the ECWES demonstrates the pilot’s effectiveness. What is especially notable was the significant increase in the decision-making dimension as well as in overall commitment to the organization. Research in the area of shared decision making has found that when teachers believe their input matters in decisions related to classroom practices and center-wide goals, they are more committed to implementing program goals and to the organization (Bloom, 2016; Allensworth, 2012). Our findings appear to support previous research in this area. Shared decision making was not the focus of the content of the professional learning provided nor was it an intentional outcome of the pilot. The significant increases in shared decision making and commitment to the organization were likely the result of embedding systems of continuous quality improvement at the classroom and organizational levels. Two of the components of the pilot, described in more detail below, focused on iterative cycles of quality improvement based on data.

Plan Do Review Cycles

To embed a system of CQI at the classroom level, administrators were introduced to the Plan Do Review process. The Plan Do Review process involves the classroom teachers and administrator meeting monthly to collaboratively identify an area of focus for improvement, choose specific action steps to take, do the work, then reflect and celebrate, make adjustments, and document the work. Administrators had to intentionally schedule time to meet with teaching staff each month to complete this work. All reflections and new goals were documented on the Plan Do Review Meeting Template each month and submitted to the Governor’s Office of Early Childhood Development. This structure helped keep the administrators accountable to the process of meeting regularly with staff to improve the quality in the classrooms.

All centers started the Plan Do Review process with the two classrooms that had received formal ERS assessments as well as assessor feedback and coaching. The teachers used their ECERS-3 and ITERS-R assessment feedback to choose their areas of focus and make improvements. Over time, additional formal and informal assessment data were collected. Using that data, the Plan Do Review process was introduced in other classrooms, used at the organizational level with items from the Program Administration Scale, Second Edition, and three centers used their work with the Pyramid Model as the foundation of their Plan Do Review work. All center administrators complied with meeting with teaching staff and submitting a minimum of ten Plan Do Review reports each year.

Nearly all respondents (97%, n = 30) indicated that teachers had participated in shared decision making during the Plan Do Review meetings. When asked to describe the impact of shared decision making, all 27 participants who provided a comment described improved teamwork, buy-in to the center’s mission, and empowerment of staff. Representative comments include:

Leadership Coaching

A Leadership Coach provided monthly relationship-based professional development with center administrators focused on leadership skills development and embedding CQI practices at the personal and professional levels. Using the individual data from the Administrator Role Perception Survey (ARPS) and the organizational data from the Early Childhood Work Environment Survey (ECWES), all administrators set goals using a documented Individual Leadership Development Plan (ILDP). The goals focused on advancing their education and credentials, advancing their leadership skills (ARPS), and embedding CQI practices throughout their organizations to improve the work environment (ECWES). Throughout the month, administrators would do the work to make progress on their goals and embed CQI in the organization. During the monthly coaching meetings, the coach and administrator reviewed the ILDP documentation, reported on incremental steps taken each month, reflected on the work accomplished, celebrated successes, and discussed challenges or barriers to getting the work accomplished.

It is notable that 84% of respondents (n = 26) indicated that their work was positively impacted by the leadership coaching. Representative comments regarding the usefulness of leadership coaching include:

Implications for Further Study and for Policy

The ExceleRate Pilot field tested two areas of innovation—foundational contracts for centers to support an increased number of adequately compensated and well-qualified staff and enhanced leadership and classroom supports for CQI. While the results of the evaluation are promising, they also suggest the need to further test and study scaling up in both areas of innovation. Increasing compensation and staffing through contracts alone is unlikely to reach the quality outcomes achieved through this pilot. At the same time, supports for CQI alone, without creating the mechanisms to ensure a living wage as a base and compensation parity as an imperative, would do little to stabilize the early care and education workforce. The implication for policymakers is to consider the adoption of an “and/with” strategy—ensure increased compensation and additional staffing with enhanced quality supports for leaders and teachers.

REFERENCES

Allensworth, E. (2012, Fall). Want to improve teaching? Create collaborative supportive schools. American Educator, 30-32.

Bloom, P. J. (2016). Measuring work attitudes: Technical manual for the Early Childhood Job Satisfaction Survey and Early Childhood Work Environment Survey (3rd ed.). New Horizons.

Bloom, P. J., and Abel, M. (2015). Expanding the lens: Leadership as an organizational asset. Young Children 70(2), 10-17.

Douglass, A. (2017). Leading for change in early care and education: Cultivating leadership from within. Teachers College Press.

Joo, Y. S., Magnuson, K., Duncan, G. J., Schindler, H. S., Yoshikawa, H., & Ziol-Guest, K. M. (2020). What works in early childhood education programs?: A meta–analysis of preschool enhancement programs. Early Education and Development, 31(1), 1-26.

Lee, M., & Louis, K. S. (2019). Mapping a strong school culture and linking it to sustainable school improvement. Teaching and Teacher Education, 81, 84-96.

Kirby, G., Douglass, A., Lyskawa, J., et al. (2021). Understanding leadership in early care and education: A literature review. Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/understanding-leadership-ECE-march-2021.pdf

Talan, T. N., Bloom, P. J., & Kelton, R. (2014). Building the leadership capacity of early childhood directors: An evaluation of a leadership development model. Early Childhood Research and Practice, 16(1 & 2). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1045231.pdf