This document may be printed, photocopied, and disseminated freely with attribution. All content is the property of the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership.

The field of early childhood education and care (ECEC) has an undeniable educator retention problem (NAEYC, 2021)A. Staffing shortages in programs have a detrimental impact on the children and families served, the communities in which they are located, and the well-being of the remaining staff. While the field’s administrator retention crisis is less publicized, it is arguably no less important. In fact, nearly a quarter (23%) of directors/administrators who responded to NAEYC’s 2021 survey reported that they were considering leaving or closing their child care program within the next year (NAEYC, 2021). Additionally, across all workforce roles, those who are new to their roles or the ECEC field are at an even greater risk of leaving, with 45% of respondents who had been in the field for a year or less and 34% of those with 2-5 years of experience reporting that they were considering leaving (NAEYC, 2021).

Administrators are the gatekeepers to program quality and the linchpin for an array of program functions that impact staff satisfaction and retention, including hiring and orienting new staff, supervising and promoting current staff, managing program finances, creating a shared mission and vision, and setting the overall tone for the organizational climate (Bloom & Abel, 2015; Doherty et al., 2015; Douglass, 2019; Sims et al., 2015; Talan et al., 2014). Moreover, research in the K-12 education sector has repeatedly found that principal turnover is tied to teacher turnover (e.g., Béteille et al., 2012; Buckman, 2021; Miller, 2013). While there is limited research on this relationship within the ECEC field, there is no reason to think the pattern would differ. To compound the problem, without effective leadership, ECEC programs risk not only staff turnover and declining quality but program closure as well (Talan et al., 2014).

Most new or noviceB administrators have formal education and training in early education and child development. However, because they tend to be promoted from the ranks of the teaching workforce, they often lack the education and training in program administration and leadership needed to successfully run and sustain an ECEC organization (Talan et al., 2014). To that point, research has found that novice administrators report struggling to navigate responsibilities in areas where they have no prior experience, such as human resources, coaching and supervision, program operations, strategic planning, and fiscal management (Kelton et al., 2022). Administrators who receive early career support are more likely to remain in the field, better support staff, improve the overall quality of their programs, and continue to grow professionally.

One way in which the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership has worked to support novice ECEC administrators is through the Ready to Lead Leadership Academy (RTL). RTL was created in 2018 as an intensive, four-month leadership academy to meet the unique needs of new and novice early childhood administrators. RTL content covers the power of reflection and self-awareness, leadership in action, transitioning from peer to supervisor, productivity and time management, and strategies for creating a balanced workload. Additionally, the RTL curriculum was strategically aligned with competencies within the Illinois Director Credential, part of the Illinois Gateways to Opportunity professional development system.

To date, the McCormick Center has conducted seven cohorts of RTL with 119 novice administrators from across Illinois completing the academy. At the conclusion of the seventh cohort, the McCormick Center engaged Erikson Institute to conduct an external evaluation report on the effectiveness of the RTL academy (Hadi-Tabassum & Beaudoin Ryan, 2023). This research brief focuses on two of four of the main research questions addressed in the evaluation: 1) if RTL meets the unique needs of novice administrators and 2) the potential impact of RTL on administrators’ own commitment to the field, support for professional development for teaching staff, and future staff retention. The two research questions highlighted here have theoretical implications regarding staff turnover in the field. The information presented reflects key findings from the external evaluation as well as additional internal analyses of the data by McCormick Center staff.

METHODS

Sample. Ninety-seven percent of RTL participants identified as female. The majority (46%) were in their thirties, close to 15% were in their late twenties, 22% were in their forties, and 17% were in their fifties. Thirty-five percent of participants identified as White, 25% as Black or African American, 26% as Multiracial, 7% as Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, 2% as Asian, 1% as American Indian or Alaska Native, and 4% identified as Other. Additionally, 7% of participants who provided information on ethnicity identified as Hispanic or Latinx. Years of early childhood experience ranged from less than one to 38, with an average of 13 years in the ECEC field, and all participants were within their first five years as an administrator. At the onset of RTL, 43% of participants reported their highest level of formal education to be a bachelor’s degree, 27% an associate degree, 24% a master’s degree, and 5% a high school diploma or GED. Close to 73% had formal education in child development/early childhood education; however, only 16% reported having a state or national administrator credential.

An important goal of RTL was to target diverse communities across Illinois; therefore, cohorts were launched in several geographic areas. Thirty-four participants were located in communities around the western suburb of Lisle. Nineteen participants were in communities on the southwest side of Chicago. Sixteen participants were located in communities on Chicago’s near west side. Additionally, 50 participants were located in counties in southern Illinois. Forty-seven percent of the programs were for-profit, and 53% were nonprofit. Thirty-four percent of the programs received Head Start or Early Head Start funding, and 41% received state Pre-k funding. Due to the pandemic, 31 participants (cohorts 1 and 2) engaged in a fully in-person RTL model, 32 engaged in a fully online-via-Zoom model (cohorts 3 and 4), and 53 engaged in a hybrid model (cohorts 5, 6, and 7).

MEASURES

Administrator Role Perception Survey (ARPS). The ARPS is a 25-minute survey for center-based program administrators. The ARPS identifies administrators’ developmental career stages based on their perceptions of mastery of key early childhood program leadership competencies. The ARPS also provides information regarding administrators’ internalized practices, levels of self-efficacy, and competencies in 36 areas across the three Whole Leadership domains.

Final Evaluation Survey. A final evaluation survey was administered online after the conclusion of RTL for cohorts three through seven. Participants were asked to provide feedback regarding their experience with various components of the leadership academy, perceived areas of professional growth, and information regarding the role of the leadership academy in their professional journey. Data from the final evaluations provided a global reflection on the overall leadership academy as well as detailed participant feedback related to specific components of the academy and the identification of targeted areas for future improvement.

KEY FINDINGS

Q1: How well does RTL meet the needs of novice administrators?

Prior to the first RTL session, participants were asked to reflect back on their thoughts and feelings when they assumed their administrative position. Data revealed that the majority (71%) of administrators entered their roles feeling unprepared for the types of issues they faced and with the hope that no one would find out how scared they were (58%). Over a third reported that their expectations for themselves were unrealistic, and 40% worried that teachers and families would not like them.

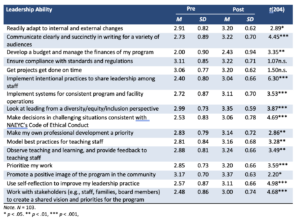

Pre- and post-ARPS asked administrators about their confidence levels in specific areas that are critical for leaders to master in order to retain staff and support and sustain quality in their ECEC program. At the start of RTL, administrators reported having the least confidence in budgeting and fiscal management, implementing practices to share leadership, and creating a shared program vision and priorities. However, a number of notable areas, including those initially rated the lowest, showed statistically significant gains at the conclusion of RTL (see Table 1).

Data also found statistically significant gains in competency in a number of important areas, including between:

Additionally, ARPS pre- and post-comparisons examined gains in each of the three Whole Leadership domains and found statistically significant increases in all three as well as an overall increase (see Table 2).

Across all seven cohorts, there were 168 RTL applicants, 142 of whom were accepted. Of those accepted 127 enrolled for RTL and 119 completed the leadership academy resulting in a 94% completion rate. Taken together, the above findings support the notion that novice center administrators have unique professional development needs and that RTL was successful in meeting those needs.

Q2: What is the potential impact of RTL on administrators’ own commitment to the field, support for professional development for teaching staff, and practices to support staff retention?

Administrator commitment to the field. ARPS data revealed that at the conclusion of RTL, 94% of RTL graduates reported that they intended to work as an ECEC administrator for at least three more years. This is a striking finding given the alarming rates of turnover in the field, especially when compared to the 2021 NAEYC survey results. Sixty-one percent of final evaluation survey respondents also reported that the statement, “I am more passionate about my work,” was either quite a bit or completely true. Moreover, 100% of respondents felt that the statement, “I am more committed to my program and my work,” was true. Lastly, participants demonstrated a deep interest in continued professional growth, with 49% reporting that they were very likely to enroll in new college coursework and 71% reporting that they were very likely to apply for a new director credential.

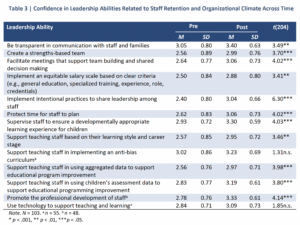

Practices to support the professional development of teaching staff and employee retention efforts. Final evaluation responses showed that 100% of RTL participants felt they had increased the reflective practices at their program. In comparisons between pre- and post-ARPS data, participants also showed statistically significant gains in confidence in practices related to improving organizational health, including the implementation of an equitable salary scale based on clear criteria. Additionally, there were statistically significant gains related to distributed leadership among staff and job-embedded practices for supporting the professional growth of teaching staff (see Table 3).

It is commonly accepted that equitable pay is one of the strongest predictors of employee retention in the field of ECEC. While RTL did not have the means to increase staff salaries directly, it is worth noting that increased competence in implementing an equitable salary scale along with a deeper understanding and commitment to self as well as staff professional development may indirectly impact compensation and, thus, employee retention.

DISCUSSION

Professional development needs of program administrators differ by career stage, with novice administrators needing targeted support in the realm of leadership essentials—the foundational competencies needed to build or maintain a thriving organization and lead quality improvement efforts at the classroom, program, and organizational levels (Kelton, et al., 2022; Talan et al., 2014). Now more than ever, it is imperative that the field of ECEC develop innovative approaches to meet the professional development needs of administrators in ways that align with their career stage and offer practical application of the knowledge and skills needed to keep programs operational and retain the workforce. RTL appears to be one model that has demonstrated the ability to meet the unique needs of novice administrators and likely enhance program sustainability through the acquisition of skills in areas of human resources, staff coaching and supervision, program operations, strategic planning, and fiscal management. While this study is limited in scope and does not include any longitudinal data on retention, it is reasonable to hypothesize that increased levels of confidence and mastery of these foundational competencies will aid in the retention of leaders and teaching staff, the satisfaction of program staff, and the overall quality and sustainability of programs.

A The NAEYC survey defined staffing shortage as having at least one open role unfilled for at least one month.

B Novice Administrators refers to those who have less than five years of experience in their role as an ECEC administrator.

REFERENCES

Béteille T., Kalogrides, D., & Loeb, S. (2011). Stepping stones: Principal career paths and school outcomes. Social Science Research, 41, 904–919.

Bloom, P. J., & Abel, M. (2015). Expanding the lens: Leadership as an organizational asset. Young Children 70(2). https://www.naeyc.org/resources/pubs/yc/may2015/expanding-the-lens

Buckman, D. (2021). The influence of principal retention and principal turnover on teacher turnover. Journal of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies, 5.

Doherty, G., McCormick Ferguson, T., Ressler, G., & Lomotey, J. (2015). Enhancing child care quality by director training and collegial mentoring. Early Childhood Research and Practice 17(1). http://ecrp.uiuc.edu/v17n1/doherty.html

Douglass, A. (2019). Leadership for quality early childhood education and care. Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD): Working Paper #211. http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=EDU/WKP(2019)19&docLanguage=En

Hadi-Tabassum, S. & Beaudoin Ryan, L (2023). 2023 Evaluation report for the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership at National Louis University (NLU): The Ready to Lead academy. Erikson Institute.

Han, M., Buell, M., Hallam, R., & Hooper, A. (2021). An intensive professional development in family child care: A promising approach. International Journal of Early Years Education, DOI:10.1080/09669760.2021.1914558. http://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2021.1914558

Hashikawa, A., Sells, J., DeJonge, P., Alkon, A., Martin, E., & Shope, T. (2020). Child care in the time of coronavirus disease-19: A period of challenge and opportunity. Journal of Pediatrics. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7366077/

Kelton, R., Talan, T., & Magid, M. (2022, Fall). Meeting the need for intensive and cohesive professional development during challenging times. Research Brief. McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership at National Louis University.

National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC). (2021, July). Progress and peril: Child care at a crossroads. NAEYC.

McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership (Summer 2018). Director’s professional development needs differ by developmental stage. Research Notes. Chicago, IL: National Louis University. https://mccormickcenter.nl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ResearchNote_July2018.pdf

Miller, A. (2009). Principal turnover, student achievement, and teacher retention. Princeton University: NJ.

Sims, M., Forrest, R., Semann, A., & Slattery, C. (2015). Conceptions of early childhood leadership: Driving new professionalism? International Journal of Leadership in Education: Theory and Practice 18(2). http://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2014.962101

Talan, T., Bloom, P. J., & Kelton, R. (2014). Building the Leadership Capacity of Early Childhood Directors: An Evaluation of a Leadership Development Model. Early Childhood Research and Practice. 16(1). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1045231.pdf