Stark Contrast between Early Childhood Program Directors and Elementary School Principals

by McCormick Center

Download

This document may be printed, photocopied, and disseminated freely with attribution. All content is the property of the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership.

This resource is part of our Research Notes series.

Two new tools that provide information about early childhood leadership were launched this summer. Concurrent with the development and release of the McCormick Center’s L.E.A.D. Early Childhood Clearinghouse,1 New America created a data visualization tool, the Pre-K Leader Policy Scan.2 Both organizations collaborated on data collection and analysis to reduce duplication and serve stakeholders with comprehensive interactive websites. They also published research reports that drew from the rich and extensive data found within the tools.

New America’s report, A Tale of Two Pre-K Leaders: How State Policies for Center Directors and Principals Leading Pre-K Programs Differ, and Why They Shouldn’t,3 written by Abbie Lieberman, highlights the contrast between the qualifications for early childhood program directors and those of elementary school principals. Lieberman found that standards for center directors were much lower than those of elementary school principals even though the requirements for their jobs were similar. While this finding is not surprising, the report comprehensively demonstrates a pervasive gap between the child care and public school sectors.

DATA COLLECTION

As a framework for assessing the pre-K leadership landscape, New America looked to “Knowledge and Competencies for Leadership in Settings with Children Birth Through Age 8” in the Institute of Medicine and National Research Council report, Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth Through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation.4 Several of these competencies align with the Whole Leadership Framework5 including teaching practices that help children learn, authentic child assessment, fostering a professional workforce, meaningful appraisal of teachers’ performance, strong community partnerships, and organizational development. These competencies point to the similarity of what is required of administrators in both child care centers and pre-K-12 schools.

New America’s Early & Elementary Education Policy team conducted a 50-state survey of departments of education (DOE) and a few state elementary school principal associations to scan the policy landscape of elementary school principals. They partnered with the McCormick Center, who collected data on early childhood center directors by examining source documents on state policies and surveying various state departments (other than DOE) for certain indicators. To more deeply understand leaders’ roles, challenges, professional preparation, and supports, New America interviewed center directors and principals across the country giving voice to their perspectives.

RESULTS

Four aspects of pre-K leadership were examined in the New America study: pre-service requirements, in-service requirements, compensation and retention, and leader diversity. New America noted the challenges of collecting data within the two sectors and the complexity of data systems, particularly in the child care sector. The report examined states’ pre-service requirements for principals with six indicators:

- Minimum education requirements

- Grade span of the principal’s license

- Coursework around early learning and/or child development

- Prior teaching experience – number of years

- Prior teaching experience – grades taught

- Clinical experiences in preparation programs

The study looked at pre-service requirements for center directors with four indicators:

- Education requirements in licensing standards

- Experience requirements in licensing standards

- State-recognized center director credentials

- Director credentials required in licensing standards

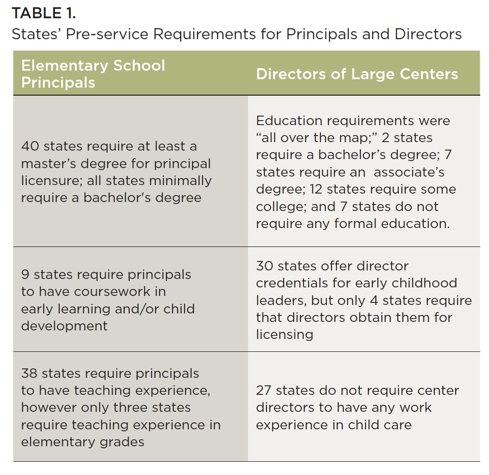

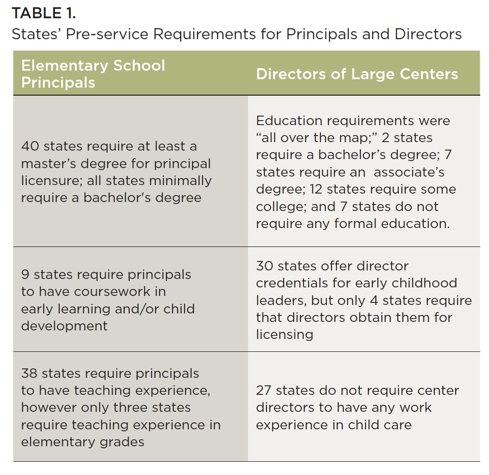

Pre-service requirements of principals were significantly higher than those of center directors. However, most states are slow to establish policies that require principals to acquire leadership knowledge and skills specific to pre-K children. Researchers found that licensing standards for center directors were inconsistent across the states and lacked rigor. Table 1 shows some highlights from the report that demonstrate the contrast between elementary school principals and child care center directors.

New America included case studies of innovative professional learning opportunities for principals, with a focus on pre-K to 3rd grade alignment. Twelve states reported having similar programs for principals. The report also highlighted professional development through tiered quality rating and improvement systems (QRIS) for child care center directors. Researchers noted that in all states, principals were required to have formal performance reviews, but no state system exists to ensure formal evaluation of center directors.

Findings were presented on compensation and retention from states where data were available. The disparity of average salaries across sectors were particularly acute. The average salary for elementary school principals was $90,410 (range $67,890 – $124,560), while that of center directors was $52,760 (range $39,190 – $68,180). Turnover for both principals and center directors was reported to be high.

New America found that 80 percent of principals were white; however, racial statistics were not available specifically for center directors. The Center for the Study of Child Care Employment reports that the overall child care workforce is more ethnically diverse than K-12 teachers. No states reported initiatives to increase the diversity of school principals or center directors.

RECOMMENDATIONS

New America recommended that states would benefit from recognizing the similarities that exist in the roles of child care and elementary school administrators. Cross-sector professional learning opportunities where principals and center directors could build relationships and coordinate efforts would help children and families as they transition along the pre-K to 3rd grade education continuum. The report put forth the following recommendations:

For Elementary School Principals

-

Embed early childhood education throughout principal preparation courses.

-

Require teaching experience or clinical experience specifically in elementary schools.

-

Offer ongoing professional learning opportunities on early education.

-

Track principal turnover and salaries and use the data to determine how districts can better support leaders.

For Pre-K Center Directors

-

Increase center director qualifications to reflect the research on child development and early learning.

-

Increase infrastructure for child care to improve center director well-being and retention.

-

Increase center directors’ opportunities for professional learning.

-

Streamline state regulations and eliminate redundancies.

REFERENCES

- http://mccormickcenter.nl.edu/lead/closing-the-leadership-gap/

- https://www.newamerica.org/in-depth/pre-k-leaders/

- The report carries a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license; full legal code at creativecommons.org.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) and National Research Council (NRC) (2015). Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth Through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 344–345).

- Abel, M. B., Talan, T. N., & Masterson, M. (2017, Jan/Feb). Whole leadership:A framework for early childhood programs. Exchange, 39 (233), 22–25.